Where do you even start with designing ethically?

A big part of my job is to create the environments for ethical innovation at the Ö÷²¥´óÐã. Rather than providing pre-established moral formulas for others to adopt, I'm more interested in creating the conditions for ethical design to happen. But what are those conditions?

To answer this question, it's helpful to think about how things usually go wrong. What are the premises that lead to harmful digital experiences?

Of course, there's no straightforward answer. For a start, we know that companies (especially big ones like the Ö÷²¥´óÐã) don't operate in isolation, but embedded in a complex network of entities including suppliers, regulators, business partners, consultants, and end-users. And while the Ö÷²¥´óÐã takes ownership for the entirety of its output, moral responsibility is often distributed among all of those entities. In other words, you're only as virtuous as the most villainous of your allies.

We also know that technology isn't neutral. But, to paraphrase Kranzberg's first law of technology, neither is it all good or all bad. Technology amplifies human behaviours rather than creating them from scratch and that means, as creators of technological solutions, some things are simply outside of our control. But some factors can be influenced, and others are entirely within our gift. And I'm most interested in the latter.

Some common culprits for harmful digital experiences

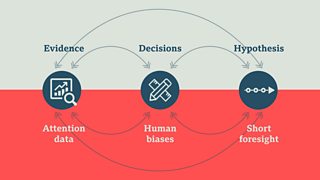

So, let's consider what's within our gift by looking at the way we design and build things. Usually, it involves shifting our mindset between past, present, and future. First we look at the past for data to fuel and frame our creative challenges and to set the success measures we aim for. In our present, we make decisions which are represented in our 'live' products. Then we set our hypothesis for how our future should look, and define the steps to take us there.

This is, of course, a nonlinear process. We constantly fluctuate between those different 'time frames'. Some projects start with a hypothesis, some others with the creative spark that comes from prototyping for example.

The fertile ground for ethically questionable designs usually emerges when three conditions (one for each stage) interplay with each other:

- We solely focus on attention data, optimising design exclusively to maximise usage of our products.

- We glorify a culture of 'fast design', when we're constantly asked to think on our feet, act first and reflect later. This creates the ideal condition for our biases to surface and spread via our design solutions.

- We suffer from 'short foresight', focusing exclusively on the now or super-near future, ignoring how our contexts change and the possible unintended consequences of our actions. Sounds familiar?

Probably much of what we're witnessing today - pre-existing biases in training data, election hijacking, social polarisation, mental wellbeing issues - is connected, amplified, sometimes triggered by technology that has been developed following this model.

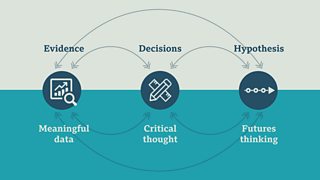

Meaningful data, critical thought, and futures thinking

The three root causes of ethically questionable design are the starting point for identifying our approach for ethical experiences. That led us to identify three pillars: meaningful metrics, critical thought, and futures thinking.

First, meaningful metrics. Imagine what would happen if we expanded our success metrics beyond attention data, to also include real human and societal value. Our colleagues in R&D are developing a fantastic set of 'human values'. We're already routinely looking at those values for design inspiration, and we're now in the process of figuring out how to turn these into KPIs. We're not there yet, but we're doing lots of thinking and experimentation in this area.

Second, critical thought. What would happen if we redesigned our processes so that reflection and critical thinking would find their space alongside intuition and creativity? We've been experimenting with 'slow sprints' as a way to combine reflective practices with design thinking. And we've been collaborating with our colleagues from policy, editorial, R&D, and other departments to work on guidelines such as the newly launched Machine Learning Engine Principles.

Finally, futures thinking. What would happen if we were to exercise our public imagination more often, getting together recurrently to imagine future stages of our world, and the unintended consequences of our solutions? We've been expanding our design toolkit to include future-casting and speculative design methods, and we've been using those as a foundation to push our thinking beyond our usual time horizons.

This is of course an approach that requires a culture change, so we're not implementing it all at once. It's also a prototype in itself, so we're learning and adapting it as we are experimenting with some of these new tools and principles. We don't claim to have all the answers, but we're at least confident that we're asking (some of) the right questions.

At the Ö÷²¥´óÐã we take our very seriously. We're here to provide real societal value, not to serve individual interests. As human-centred designers working in an organisation like this, we're here to constantly re-learn, adapt and challenge our own ways of working, pushing ourselves and our discipline in a constant quest to find new ways to serve society the best we can.