As an IA (Information Architect) at the Ö÷˛Ą´óĐă, it's my job to make the complex and complicated easier to make sense of. We don't just do this for audiences. Often during projects, we need to help multidisciplinary teams work together and unravel complex challenges. One of the best ways to achieve this is through visual representation. When you're lost in the world, it's natural to turn to a map. In creative projects, we make maps to help us find our way towards the best solution.

There are lots of different ways we can map stuff out, but in this article I'm going to concentrate on spatial mapping. This type of map generally doesn't follow a single linear path with a definitive beginning or end. Much like a metro map, it supports multiple relationships and paths.

Of course, we don't draw metro maps to help our design teams here at the Ö÷˛Ą´óĐă. But we use the same principles to illustrate navigational routes through products or complex structures.

Embracing constraints

A spatial map is a really straightforward concept. At its core is a visual representation of a list of different things and the relationships between them. The key is to keep it simple. It's important to consider carefully what to include in that list of things, lest it becomes so big it undermines the purpose of creating the map.

A perfect example of embracing constraints within a spatial map is the transport map. Way back in 1931, Harry Beck revolutionised the way we navigate public transport when he created the London Underground Map. Beck took the existing map and removed geographic dependencies and unnecessary details. This transformed a complicated and unloved chart into a clear and simple narrative. It also created a work of art. It's what the map doesn't show that makes it so easy to navigate and why it became the basis for most urban rail transport maps around the world today.

Mapping things and the relationships that connect them

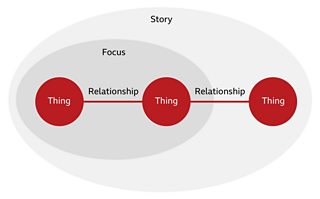

When creating your own spatial maps, the things can be anything you want them to be. But it's the map that lets you explore and describe the relationships between them. Probably the best way to demonstrate this is by mapping out an actual spatial map. In fact, the map below is a spatial map of a spatial map.

This is the fundamental basis of how we create our spatial maps. Our various things are connected together by their relationships. How we organise them tells the story our map is designed to portray.

Finding the story's focus

But in order to tell the story effectively, you may need a little more focus. By adding a focus, you can impose a perspective that leads the viewer to where you want them to be.

This focus could be quite literally represented on the map. For example, the 'You are here' spot found on many maps in national parks or wildlife areas where there are no cross streets to use as reference points, clearly adds focus.

This focal point could also be the heart of the story your map is trying to tell. Think of a map that shows all the ways different elements can interact with a database. Perhaps that database is at the heart of your map and therefore represented as the focal point.

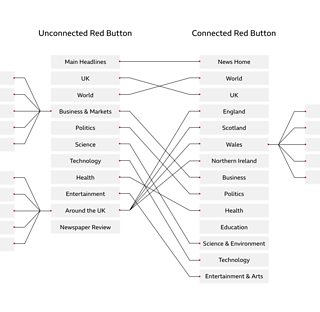

But the focus can also be considerably more abstract. For example, I created a map for the Ö÷˛Ą´óĐă to show routes to content in all the various products within the Ö÷˛Ą´óĐă's Red Button. These routes were the core story the map told. However, you may know there are two versions of the Red Button service. One used by televisions that have no connection to the Internet (and often mistakenly called Teletext or Ceefax) and another version for connected Smart TVs.

While both versions essentially have the same goal, there are navigational disparities between them. So, we created a map that not only told the story of routes to content in both versions, but also highlighted the disparity between them. That disparity became the focus of the map's story and revealed hidden details that helped us make decisions. Understanding where the focus is when you design your map will allow you to decisively create intent.

Understanding where the focus is when you design your map will allow you to decisively create intent

Iteration and refinement

The final stage of creating useful spatial maps is to work with your stakeholders and end users, then iterate and refine your designs. In the end, the map must clearly serve its intended purpose. There's no point in spending weeks drawing a complicated schematic only to find your stakeholders struggle to understand the map.

By following these four basic rules when creating spatial maps, you can create beautiful and useful maps that help your teams navigate complicated systems and complex problems.

- Embrace insightful constraints when selecting which things should be on your map

- Consider useful relationships between those things

- Plan for a clear story and focus

- Iterate and communicate with stakeholders