How often do we have the opportunity to conduct user research with an entirely new interaction domain? As human-centered design professionals we're used to people's context changing all the time. Thankfully, their devices and means of interaction stay pretty constant.

Now imagine coupling a new set of interactions with an existing app experience. In this case, bringing interactive 3D models out from behind a screen and into a shared physical space. How might the user's relationship with that content change? And how might we as designers use physical space to enhance the experience?

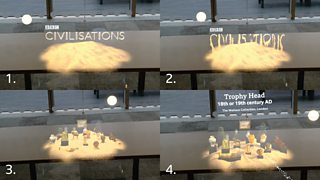

During summer 2019, we had the opportunity to evaluate an early version of �������� Civilisations built for Magic Leap 1, one of the devices in the spatial computing sector. Before we tell you all about what we learned, it makes sense to share some recent history.

Background

In early 2018, �������� R&D launched the ��������'s first audience facing app with augmented reality as part of its core experience. To date, it has been downloaded over a million times in countries right across the globe. Just over a year after its release, our partners at worked to reimagine the Civilisations experience for the next evolution of AR technology.

For the original Civilisations project, �������� Arts & Culture partnered with museums and institutions across the UK. They used cutting-edge technology to 3D-scan and digitise over 60 historical artefacts that were then accessible via the mobile app. Users can position each artefact in their own space and explore it through the "magic window" of their smartphone. They can discover deeper information about the artefact through spatial hotspots, delivered through an audio voiceover and overlay text on their mobile screen.

Devices

There are some early AR headsets already out in the wild that could help bring the Civilisations experience even closer to users. Two of the most notable examples are the and . Both allow digital objects to be projected spatially into the real world.

were funded as part of the Magic Leap Independent Creator Program to rethink Civilisations for the Magic Leap 1. This naturally creates a pile of opportunities over using a mobile device or tablet when exploring 3D artefacts. For instance, it enables objects to be viewed stereoscopically, meaning users get a sense of depth that their smartphone can't replicate. The headset is also paired with a handheld controller, meaning users can effectively "touch" artefacts directly, rather than just interacting through taps and swipes on a screen.

Conducting Research Sessions

We were painfully aware of our lack of experience facilitating sessions with this kind of technology. To reduce ambiguity, we decided to run some "expert evaluations" with our �������� colleagues. By doing this, we hoped to:

- Understand the "flow" of a session

- Test battery life

- Broadly investigate their response to the experience

- Identify any immediate usability barriers

Essentially, we piloted the research session in a low impact way to minimise mistakes we might make when it came to the real thing. We learned a ton of things that made the research entirely unique from web or mobile based research, including:

1. You can't just look over your user's shoulder…

Firstly (and most importantly), we were entirely blind as to what the user could see through the lenses of the Magic Leap 1. We're used to encouraging users to narrate their thoughts aloud during usability sessions; but asking them to also describe what they could see added an extra layer of complexity. This made it much more difficult for us to probe their thoughts and feelings with appropriate questions. On top of this, you might even have to chase them around the room as they explore the experience, so a clipboard might come in handy!

2. You can't just switch to another device

If your device fails during a desktop or mobile based test, often it's easy to switch to a backup. If you're using a web-based prototyping tool it's just a case of opening the link on another device. We only had a single headset with an on-board prototype, so didn't have this luxury. This is also why we were testing battery life, so we could see how long might be needed between sessions to give the device a power boost.

3. Your physical environment might affect the tech

The original room we reserved had minimal natural light and shiny whiteboards on the walls. This hampered the device's ability to understand the environment, and therefore made it less able to place 3D objects as seamlessly in the real world. Thankfully, we tested the room out a few days beforehand so switched to another in time for the expert evaluations.

The Real Thing

When evaluating the Civilisations mobile app, we partnered with to facilitate our research sessions. It made sense to use their expertise, not least because they have a purpose built research lab:

Taking what we'd learned during our pilot sessions, we made sure to borrow a backup device from Nexus. This meant we wouldn't have to worry if the battery died after a few sessions, but also had something to fall back on in case of an unforeseen technical issue.

Our facilitator also made it possible to stream a video feed of the user's point of view. This meant they could check in on what the user could see whilst facilitating, but also meant we could observe remotely from a second room.

What we learned

In short, a lot — far too much for a snappy blog post to encompass! There were some prominent threads we want to follow up on though.

1. People don't intuitively understand that they can use the space around them

One of the most exciting things about bringing Civilisations to Magic Leap is the opportunity to place artefacts in your world and explore them at real scale. Following a spatial "splash screen", users were given a 3D menu of miniaturised artefacts to select from.

Many users would interact with the artefacts at the table, but didn't try to bring them "out" into the world until we explicitly told them they could.

2. People won't naturally understand their body is an input mechanism

A large part of the Civilisations experience is the rich audio information that describes the history of each artefact. In the Magic Leap experience, we intended this audio to be triggered when a user walked into any number of floating spatial "hotspots" positioned around the artefact.

Precisely zero of our users understood that walking into these glowing balls of fire was what started the audio. Every single user pointed the controller at the hotspot and pressed the trigger.

In hindsight, this makes complete sense. The experience begins with users pressing the trigger to place the artefacts on the table. They then pressed the trigger to drag an artefact into the world. It shouldn't have surprised us that when asked to interact with the floating hotspots, users also tried pressing the trigger!

As user experience designers, we're well versed in creating interfaces which are useful and elegant - though usually pretty explicit. With experiences that are spatial and immersive we have the opportunity to weave interactive elements around the user more naturally. There's not so much of a legacy in terms of convention—which is liberating! But it also comes with responsibility: we need to craft enchanting, natural cues and affordances but they have to still be usable.

3. People will expect real world behaviour of spatial tools

Some of the artefacts in Civilisations have enhanced information, revealed through a "magnifying glass" tool. For instance, the Egyptian sarcophagus can be X-rayed to view the mummified corpse inside:

The magnifying glass also allows users to see a "restored" view of some other artefacts. We picked the magnifying glass because we:

- Didn't want to have two separate tools for the "X-ray" and "Restore" functions, and

- Wanted a tool that users would intuitively know how to use

Lots of our users remarked that the magnifying glass didn't actually magnify anything - which is a feature they would have liked! Perhaps if we need to design a multi-use tool we need to break existing conventions and invent something completely new, maybe some kind of sonic screwdriver? 😉

Conclusions

When conducting research with new technology, it's easy to focus on the constraints of the device in use. Don't get us wrong, constraints are important - they help us focus on what the technology can actually do and avoid us pushing too hard for something that is doomed to be a bad experience. At the same time, making mistakes while the technology is still developing does create some tangible threads to follow in service of good spatial immersive design. Before head-mounted augmented reality becomes more pervasive, we want to develop best practices that can apply across all spatially aware technologies (whether they exist yet or not). Of course, new capabilities will emerge that force us to re-examine what's practical. For now, we're grateful to have a user-centered starting point, and will share where these threads lead us.

If you're interested in hearing more about spatial & immersive design or have any thoughts about our research, please join the conversation on .