Eight things we learned from Feargal Sharkey on Political Thinking

The original lead singer with The Undertones, A&R executive, keen angler and environmental campaigner, Feargal Sharkey has packed in several lifetimes’ worth of passions. Growing up in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, Sharkey was reared by two politically aware parents who instilled in him a desire for change.

He has carried his activism into working for musicians’ rights, and now champions the cause of cleaner rivers and coastal waters through his work with the Amwell Magna Fishery and Fish Legal, including holding the Environment Agency to account over their duty to protect water quality.

On Political Thinking, Sharkey told Nick Robinson more about how his early life shaped his incredible journey.

Feargal is named after figures from IRA history

Feargal Sharkey’s real name is actually Seán Feargal Sharkey. His mother named him after Fergal O’Hanlon and Seán South who were killed while attacking a Royal Ulster Constabulary barracks in County Fermanagh in 1957 as part of the IRA’s Border Campaign. “What might that tell you about my mum's politics?” says Feargal, adding: “I'm more comfortable talking about this in the modern world.”

His father believed socialism could triumph over sectarianism

Feargal’s father, Jim, was chairman of the Labour Party in Londonderry and secretary of the local branch of the electricians’ union. He was firmly of the view that, as Feargal puts it, “the industrialists of Northern Ireland were using the axe and hatchet of sectarianism to divide the working classes and to exploit them.” Believing division to be about class rather than religion, Jim had “spent a lot of the fifties trying to reach out to the Protestant working classes and Protestant workers.”

His mother was the campaigner of the family

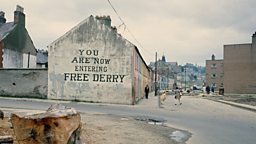

Despite his father’s credentials, Feargal believes that his mother was ultimately “the campaigner and the driver of events.” The family lived in the Bogside area of Derry and Feargal recalls how she “bundled everybody into the family car” in 1969 “and demanded Dad drove us to the other side of Ireland, where, as a family, we took part in the People’s Democracy March for civil rights between Belfast and Dublin, protesting the injustices of Northern Ireland.”

Feargal was just ten but remembers being in the middle of the march “waving very enthusiastically what I later would discover was commonly referred to as an anarchist flag. But you're ten years old, and it’s fantastic; it’s a day out!”

School offered Feargal a different kind of activism

Feargal says that the Christian Brothers school that he attended was very keen to send its students on to better things. “It quickly became apparent in my induction that if anybody thought school finished at 3pm, you were completely misinterpreting the situation,” he remembers, “and if I thought that my weekends were my own, for the next five or six years, I had really misunderstood exactly how this game worked.” Pupils were required to sign up for six clubs and societies “otherwise someone else would volunteer six in your name.” Among those chosen by Feargal were fly fishing, fly tying, hurling and debating club.

Debate was a family value

Feargal’s home life was, in many ways, already a debating club, where the unwritten rules included “calling out injustice” and “justifying your opinions.”

You were very careful - and this applied to both communities - about where you went after dark.Feargal Sharkey on growing up during The Troubles

“I was brought up in a world where, in my kitchen, the housewife, the plumber, the electrician, the bricklayer, the unemployed and the schoolteacher debated and discussed and planned civil disobedience and rebellion,” recalls Feargal, “and I watched first hand, as a 12-year-old, as they played quite a substantial part in bringing about the destruction of the government of Northern Ireland. So, in the house I grew up in, anything was possible.”

There was a climate of fear on the streets

While Feargal enjoyed freedom of expression at school and at home, as soon as he stepped outside he had to be extremely cautious.

“In those days, the 1960s, early 1970s, you were very careful - and this applied to both communities - about where you went after dark and which parts of town you were prepared to enter,” he says, “because, simply for that fact, you could end up in an awful lot of trouble.”

The answer to the question ‘what school did you go to?’ would decide, as a teenager, “whether or not you were about to be beaten up.”

Feargal says that this way of finding out whether you were Catholic or Protestant would also dictate “whether you had a future” in terms of employment. “At the time in Derry, I think about 60% of men were unemployed, and the vast majority of those, 99%, were Catholic.”

Going to Star Wars was made into a political act

Life in Derry in this period included regular body searches by the British Army. Feargal remembers that he “couldn't even walk out my front door without, within minutes, finding myself spread eagled on my fingertips with my legs being kicked back, being searched and questioned and everything else.”

These searches, Feargal says, were a “fact of life” for all male teenagers in certain areas of the city, such as the Bogside and Creggan. He recalls going to see Star Wars “when it finally came to Derry”, around 1978, but never making it because he was arrested and taken in for questioning. “That was normality. You didn't appreciate that the world lived another way.”

Be focused on what you want to achieve

Summing up his journey from his Derry upbringing to his present-day campaigning role, Feargal says that the values he was brought up with were about “being very focused on what you want to achieve and being very clear intellectually on how you can achieve it.”

What he now knows as being the essence of politics also involves: “being incredibly empathetic to the people that you're talking to and understanding their point of view and their challenges and their objectives, and trying to explore and find the commonality in that middle ground, being able to express it and narrate it, and ultimately being able to create that kind of argument where people will see the justification and the right behind the point you're trying to make and be prepared to follow up and commit themselves to achieving the same goal.”

More from �������� Radio 4

-

![]()

Profile: Feargal Sharkey

From punk rocker to eco warrior – how Feargal Sharkey became the face of the campaign against pollution of the waterways.

-

![]()

Political Thinking: The Tony Danker One

The CBI boss on being Jewish during 'The Troubles' and why everyone's a Brexiteer now.

-

![]()

Amol Rajan Interviews...

Amol Rajan interviews the era-defining pioneers, leaders and maverick thinkers who are shaping our rapidly changing 21st-century world.

-

![]()

Today

News and current affairs, sport, weather and Thought for the Day.