Our Classical Century – Five Top Pieces

Our Classical Century – a collaboration between Ö÷²¥´óÐã Four and Radio 3 which culminates at the Ö÷²¥´óÐã Proms in 2019 – examines the greatest moments in classical music in the 20th century.

As the first of four Our Classical Century seasons kicks off we've brought together complete versions of five all-time popular pieces from the music of the last hundred or so years for you to enjoy.

1. Vaughan Williams: The Lark Ascending

14 June 1921. The Queen’s Hall, London. This quiet midsummer’s evening saw the first performance of a work that would become one of the most consistently popular pieces of classical music ever written.

Ralph Vaughan Williams had composed The Lark Ascending seven years earlier, in 1914. The war intervened, and Vaughan Williams had to wait seven years to hear his meditation on a poem by George Meredith performed by an orchestra.

It was eventually performed by the British Symphony Orchestra under Adrian Boult, with the dedicatee of the work, Marie Hall, taking the swirling improvisatory sounding violin solo. One critic wrote: "It showed supreme disregard for the ways of today or yesterday. It dreamed itself along".

This Ö÷²¥´óÐã archive recording features soloist Elena Urioste performing with the Ö÷²¥´óÐã Philharmonic Orchestra with conductor Alexandre Bloch.

Discovering the Great Composers on Radio 3: find out more about Vaughan Williams.

2. George Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue

In June 1925, Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue was the sound of the summer - its sauntering clarinet glissando the sound of the decade.

The work's intoxicating cocktail of romantic lushness and jazz bravado summed up a new nation on the intersection of remembering, dreaming and scheming. Gershwin said he heard the piece as a sort of “musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness.”

Two months after the publication of F Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby, Rhapsody in Blue arrived in London at a venue that would have fit Gatsby like a glove. Gershwin performed the piano part himself in the ballroom of the glamorous Savoy Hotel: the first hotel to provide 24-hour room service, the first to host dinner dances, and the first to broadcast its house bands live on the Ö÷²¥´óÐã.

Gershwin was almost late for his performance that night because he was so engrossed in conversation with one Mr Marconi about the wonders of radio broadcasting. Marconi would turn up a decade later in one of Gershwin’s songs: "They told Marconi wireless was a phony / It's the same old cry..."

But Gershwin knew first-hand that wireless was anything but phony. Thanks to a live broadcast from the Savoy, his brave new sound of America reached way beyond the suave crowd at the Savoy that night, right into the homes of thousands of listeners.

This Ö÷²¥´óÐã archive recording features soloist Marc-Andre Hamelin with the Ö÷²¥´óÐã Scottish Symphony Orchestra and conductor Thomas Dausgaard.

Discovering the Great Composers on Radio 3: find out more about George Gershwin.

3. William Walton: Popular Song from "Façade"

The first performance of Façade, by William Walton and Edith Sitwell, took place on 12 June 1923 in the grand setting of London's Aeolian Hall. Unusually, the event wasn’t billed as a concert, but as an "entertainment" for six instruments and reciter. Walton, a gifted composer, was a hit with the bright young things of 1920s London. He had been all but adopted by the aristocratic Edith Sitwell and her brothers, Osbert and Sacheverell, who persuaded the reluctant Walton to set Edith’s poems to music.

On the night of the first performance, Sitwell spoke her lines through a "sengerfone", a decorated megaphone that protruded through a monstrous face painted on a screen (a staging decision that was as practical as it was dramatic; it meant that she could be heard above the instruments). The music itself was a fizzing mix of sophisticated jazzy modernism and music hall parody, with masses of quotations thrown in.

Evelyn Waugh and Virginia Woolf were among the first dazed audience members, while Noel Coward was so disgusted that he walked out in the middle. The reviews were mixed. While one headline denounced Façade as "drivel that they paid to hear", a more thoughtful critic wrote:"As a musical joker, [Walton] is a jewel of the first water’.

This Ö÷²¥´óÐã archive recording is by the Ö÷²¥´óÐã Symphony Orchestra with conductor Sakari Oramo.

Discovering the Great Composers on Radio 3: find out more about William Walton.

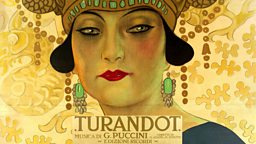

4. Puccini: In questa reggia (Turandot)

Puccini wasn’t at La Scala on the night of his opera Turandot's premiere in May 1926.

The performance ended with the most famous curtain in operatic history. In the middle of Act 3, just a couple of bars after the line "Liù, poesia!” the orchestra came to a halt and the conductor, Arturo Toscanini, turned to the audience. “Here the opera ends,” he said, “because at this point Puccini laid down his pen". And then the curtain slowly lowered. Puccini had died a year and five months earlier, before he could finish the last act of his last opera.

Turandot is a dark and politically dubious fairytale. For decades it was banned in the People's Republic of China because of what they saw as appalling ethnic stereotyping. The music is the richest, most adventurous, most dissonant and most urgent Puccini ever wrote, its harmonies avant-garde. Puccini might have had a sentimental streak, but he hadn’t failed to notice what was happening all around him.

This extract is from a recording by the Munich Radio Orchestra with conductor Roberto Abbado and soprano Eva Marton.

5. Ravel: Boléro

Audiences in 1928 were outraged by Boléro. But strangely enough, its composer agreed with them...

Later in life, Ravel couldn’t believe that his experiment in musical hypnosis, this uncompromising exercise in proto-minimalism, would become his most popular piece. He was amazed that orchestras were even prepared to play it.

The tune of Boléro – the only tune – came to Ravel while he was on holiday. Just as he was about to go for a swim, he rushed to the piano and played the melody with one finger. “Don’t you think it has an insistent quality?” he asked a friend. “I’m going to try to repeat it a number of times without any development.” And so he did. He repeated it for 340 bars.

Later he was embarrassed. “Once the idea of using only one theme was discovered,” he protested. “Any conservatory student could have done as well.” But the point was, no conservatory student did as well. And there was immense passion in this sultry, androgynous dance, a masterclass in delayed sensual gratification. And there was politics. For the staging, Ravel imagined a factory in the background. This was machine-age music, music of mechanical construction that didn’t merely comment on the condition of working people – but actually embodied modern automation.

No wonder Ravel thought orchestras would baulk at playing Boléro. Little did he know they would still be playing it nearly a hundred years later.

This archive recording is by the Ö÷²¥´óÐã Scottish Symphony Orchestra with conductor Donald Runnicles.

Discovering the Great Composers on Radio 3: find out more about Ravel.

-

![]()

Our Classical Century

These are some of 100 significant musical moments explored by Ö÷²¥´óÐã Radio 3’s Essential Classics as part of Our Classical Century, a Ö÷²¥´óÐã season celebrating a momentous 100 years in music from 1918 to 2018. Visit bbc.co.uk/ourclassicalcentury to watch and listen to all programmes in the season.

-

![]()

What is Our Classical Century?

Find out more about this season celebrating 1918 – 2018's most memorable musical moments

-

![]()

Essential Classics

Refresh your morning with a great selection of classical music, presented by Suzy Klein and Ian Skelly.

-

![]()

Our Classical Century: Watch and Listen

A selection of Radio 3 and Ö÷²¥´óÐã Four programmes from Our Classical Century.

-

![]()

Composer of the Week

Donald Macleod offers an informative and accessible guide to composers and their music.