What was really wrong with Beethoven?

While it's widely known that Ludwig van Beethoven suffered hearing loss, few people are aware of how that affected him, what might have caused it, and the fact that he was dealing with a number of other unpleasant ailments – in fact he enlisted a total of 14 physicians to try to help him.

In Radio 3's Dissecting Beethoven, with the help of a worldwide group of physicians, Georgia Mann and eminent neurosurgeon Henry Marsh reach down 250 years to Beethoven's birth, to try and solve the puzzle of the composer's numerous health problems, and how they affected the man and his music.

Roll over Beethoven

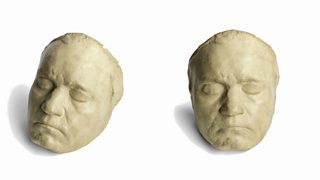

Starting at the end, Georgia and Henry look at the report of Beethoven's post-mortem, carried out by Dr. Johannes Wagner in Vienna on the day after Beethoven died, 27th March, 1827. It makes grim reading. Wagner describes being able to “pass the quill of a goose through the excretory duct of Beethoven’s pancreas.” Meanwhile, Beethoven's abdomen was described as being “distended and swollen with fluid.” Henry diagnoses the latter as ascites, the main complication of cirrhosis, and reveals that Beethoven’s liver (which ended up half its normal size, hard as leather and coloured bluish green) was regularly drained by a barber surgeon in the final months of the composer’s life.

Living through the pain

Beethoven’s deafness began around 1795 and gradually worsened as his life went on, a condition that was exacerbated by severe tinnitus. His acoustic (hearing) nerves were noted as enlarged on his autopsy. Former head of the Beethoven Center at San Jose University in California, William Meredith, explains that Beethoven started to experience abdominal problems, fevers and headaches around the same time as his hearing problems, and that these also continued throughout his life. Liver disease is also recorded, with two bouts of jaundice in 1821 and 1825, and kidney failure. Not surprisingly, Beethoven suffered from depression, latterly diagnosed as either bipolar syndrome or ADHD.

“A couple of Beethoven's friends said that he was a hypochondriac,” says Meredith, “but then when I was going through this list of symptoms, I was like, well, of course he was a hypochondriac – who wouldn't be?”

Ominous movements

One of Beethoven’s regular health complaints was troublesome bowels. His conversation books (used to communicate with friends on account of his deafness) and his letters reveal a number of references to abdominal pains, colic and diarrhoea.

Beethoven’s diet provides some clues as to why he suffered so. Food historian Ivan Day details a typical Sunday dinner of a meat stock soup with dumplings, followed by beef with caper sauce and minced turnips and then, maybe, a pigeon pie followed by roast veal and salad. The rest of the week was much the same, Day notes, adding: “We know now, better than they did in the early 19th century, that this [high meat] diet wasn't particularly good for the uric acid levels in your bloodstream and you would end up with all sorts of problems, like gout for instance.”

Considered as ahead of his time in his music, Beethoven appears to have been modern in his taste in hot beverages too. He liked his coffee and he liked it strong, starting every day by counting out exactly 60 coffee beans and grinding them himself. He was advised to cut down by one of his many physicians because of the effect on his bowels.

Drunk on more than just music

Ludwig was partial to an alcoholic beverage too. Laura Tunbridge, author of the biography Beethoven: A Life in Nine Pieces, notes that his doctors did recommended that he cut back, “which is actually quite unusual for the early 19th century because people are only just getting to grips with the medical consequences of drinking too much too often.”

Lead acetate or 'lead sugar' was, at this time, used to make bad wine taste better, and it’s likely that Beethoven was imbibing this toxic substance.

Beethoven’s friends were also concerned, particularly about his consumption of adulterated wine. Lead acetate or "lead sugar" was, at this time, used to make bad wine taste better, and it’s likely that Beethoven was imbibing this toxic substance. This appears to have been borne out by posthumous tests on his hair showing traces of lead in it.

Curative quirks

In the face of all his health issues, Beethoven did not have much in the way of effective treatment options. Doctors simply diagnosed on the basis of urine, faeces and how the patient appeared, while, as Henry Marsh points out, “the therapeutic manipulations were bleeding and leeches, particularly around the anus.”

Dr Frank, Beethoven’s first doctor, prescribed warm olive oil for his ear complaints, a method still used today. Another doctor treated Beethoven by blistering his arms, but this was painful and prevented him from playing the piano. His favourite doctor, Dr Schmidt, sent him to the spa in Heiligenstadt, now part of Vienna, in 1802, and treated him with leeches. Other doctors prescribed baths on the basis of the medical theory of "humorism" that defined health as a balance between body liquids (bile, blood, phlegm). Related treatments included massage, applying peat moss around joints, poultices, gargling or drinking the waters, and fluids inserted into the vagina or the rectum.

Mood music

The gravity of the health struggles that Beethoven faced very likely had a bearing on his art. Some doctors and musicologists think that the unfortunate composer suffered from cardiac arrhythmias, on top of everything else, and that the tautness of this was reflected in passages of his music, e.g. the cavatina from the String Quartet No. 13. Brodsky Quartet cellist Jacqueline Thomas also points to the bow control needed for the emotive "Holy Song of Thanksgiving" in his Op. 132 String Quartet, written two years before his death.

That his illnesses caused Beethoven torment is undeniable. In a letter to his brothers, he wrote:

“Oh you men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic. How greatly do you wrong me? You do not know the secret cause which makes me seem that way to you. Think that for six years now, I have been hopelessly afflicted made worse by senseless physicians from year to year, deceived with hopes of improvement, finally compelled to face the prospect of a lasting malady whose cure will take years or perhaps be impossible.”

-

![]()

Dissecting Beethoven

Georgia Mann and eminent neurosurgeon Henry Marsh explore the story of Beethoven’s health, starting with the results of Beethoven’s autopsy, which revealed a liver: "like leather... hard and bluish-green", and an abdominal cavity: "filled with four measures of rust-coloured fluid"...

Beethoven unlimited

-

![]()

Beethoven Unleashed

Programmes, concerts and features celebrating the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth.

-

![]()

Beethoven Remixed

Everything you need to know about the Beethoven's Fifth Symphony Remix challenge.

-

![]()

The Listening Service: Becoming Beethoven's Fifth

How did Beethoven compose one the most famous works in classical music?

-

![]()

Da-da-da-DAH!

Take four notes – understanding Beethoven's 5th and how to adapt its building blocks.