Eight things we learned from Robert Macfarlane's Desert Island Discs

Robert Macfarlane has written prize-winning, best-selling books about the natural world, including The Wild Places, The Old Ways and Landmarks. In 2017 he published The Lost Words, created with Jackie Morris, highlighting words such as acorn, bluebell and kingfisher, which were disappearing from British childhoods. It became a phenomenon, and has been widely adapted for performance, and distributed to schools, care homes and hospices. His most recent book, Underland, journeys to the world beneath us, including caverns and catacombs.

Here’s what we learned from his Desert Island Discs:

1. Robert loves mountains – but it’s a complex relationship

Robert grew up in a family of amateur mountaineers and spent holidays exploring the Cairngorms, nurturing a fascination which inspired Mountains of the Mind, his debut book about the history of the human engagement with mountains.

Mountains were where I wanted to be, and for a year or two they were where I thought I would die

“Mountains just seized me,” he says. “They were where I wanted to be, and for a year or two they were where I thought I would die. And that was stupid of me. But that was the force with which they had my heart and my mind.”

“There is a selfishness in extreme climbing and there's a selfishness in that summit selfie that draws people at risk of their lives to the summit of Everest every year… So there is a selfishness and a solipsism to it but there's also a self-abolition in mountains. They live in deep time in ways that absolutely dissolve human units of being and I find that humbling.”

2. His first track reveals something that Robert holds to be “an unforgettable truth”

“I think it's just utterly gorgeous,” say Robert about his first musical choice .“That voice of his, that famous voice - and lyrically I think it's one of the most perfect songs I know. It's about this sad boy who travels, melancholy and bittersweet, very far, very far, but he learns one thing: ‘the greatest thing you'll ever learn is just to love and be loved in return…’ and that seems to me an unforgettable truth,” says Robert.

The “famous voice” belongs to Nat King Cole and the song is Nature Boy, first released in 1948.

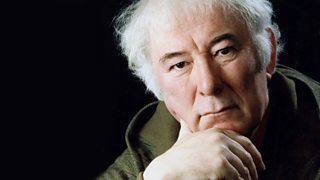

3. A handshake from a great Irish poet was a vital teenage moment

Seamus Heaney won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995, and four years before that he published a collection called Seeing Things. Robert was a sixth-former at the time, read the book and was desperate to meet its author: “I flew over to Belfast, actually, to hear Heaney read. He was an absolute rock star to me and I… went up and shook his hand afterwards. And he said a few kind words to me. And I remember, I didn't wash my hand for a week afterwards. He was showing me that language could jump around, it could live its own life, it could turn tumbles, it could turn to stone, it could turn to lightning and air, it could even represent light. And those were magical powers clearly, to a teenager.”

4. His second track is his musical metronome when out in the world

“It's my walking song,” Robert explains. “I know [the singer-songwriter of it] now, I write music with him now, but I knew this song long before I knew him and I don't think I could ever out-listen it really… It's the one I've set my pace to in the mountains, on the long paths. And his voice is just like this kind of weathered rock really, it's wise before its time.”

I would walk and teach when I was seeing students one on one and I remember thinking, 'Oh, this isn't an hour's teach, this will be a three-mile teach’

The song is Ghost of O'Donahue by singer-songwriter Johnny Flynn.

5. He wants children and the natural world around them to grow together

“Children are naturals at nature,” says Robert. “They do it far better than [adults]. They lie down in it. They eat it… I would love to see every primary school in this country twinned with a farm. I would love to see every primary school planting trees in the cities and the countryside around. Some of that is already happening, but we could do so much more of it, and in that way we grow together people and place.”

6. To bring back memories of driving to the Cairngorms, Robert chooses a Californian classic

“This track always reminds me of my dad getting over the border into Scotland,” says Robert, recalling childhood family holidays when they would drive north from their home in Nottingham, listening to music. “We'd get to the shores of Loch Lomond and we'd have been going for over six or seven hours, and he would pull the car over, leap out of the car and strip down to his pants... and leap into Loch Lomond and just sluice off the journey and be joyful at being back in Scotland. And then he’d get back in the car and we would carry on up to the mountains.”

The song is California Dreamin’ by The Mamas and Papas.

7. The Lost Words has taken on a life of its own – growing like the nature it describes

No one could have anticipated the success of The Lost Words, Robert’s book with illustrations by Jackie Morris, which focused on words which were fading out of the lives of British children – from bluebell and conker to willow and wren, via heron and kingfisher. “It's a bit like accidentally dropping an acorn out of your pocket and up springs a wild wood… Most wonderfully it's been given by grassroots campaigns up and down the country to primary and secondary schools and to care homes and to GP surgeries - places where people are either gaining words as they are as young people in primary schools, or losing them as they are often through dementia. As a writer, to see something you write become wild and go and move through the world like that is probably the greatest of thrills.”

8. He doesn’t think of himself primarily as a writer

Robert has a day job. For almost 20 years he’s been a fellow of Emmanuel College at Cambridge University, and he teaches there as part of the Faculty of English. If passports still asked for a profession, he says he would describe himself as a teacher – and during lockdown, like every teacher, he’s had to improvise and adapt. He set up his own outdoor classroom under a tree, with a tarpaulin and a few chairs. “And then I would also walk and teach when I was seeing students one on one - PhD students or undergraduates - and so I remember thinking, 'Oh, this isn't an hour's teach, this will be a three-mile teach’, measuring it in distance,” he laughs.