Psalmes, Songs and Sonnets

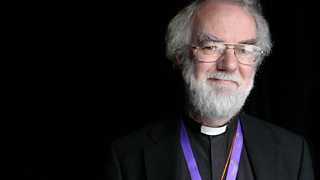

In the week of the 400th anniversary of his death, the Rev Dr Jonathan Arnold reflects on William Byrd's contribution to Christian music and worship.

William Byrd is regarded as one of England's greatest composers. He lived through turbulent times through the Sixteenth and early-Seventeenth Centuries, witnessing both significant religious and political change. Despite this, he composed some of the finest music of his time for both the Catholic and Anglican Church.

In the week of the 400th anniversary of his death, The Revd Dr Jonathan Arnold reflects on William Byrd's contribution to Christian music and worship. Jonathan visits the Church of St Peter and St Paul, Stondon Massey in rural Essex - where Byrd is thought to be buried - and also the nearby Ingatestone Hall, the home of the composer's patron, Lord Petre. Jonathan speaks to the current Lord Petre about the connection between Byrd and his patron through their Catholic faith.

Harry Christophers, founder and director of The Sixteen, reflects on the sense of longing and faith in Byrd's music, expressed in the composer's particular attention to the texts he set from scripture, and there are contributions from Byrd scholar Professor Kerry McCarthy, music historian Dr Katie Bank, and singer and conductor Dr David Allinson.

Byrd remained a Catholic throughout his life, which for many at the time was a dangerous thing to do, but his contribution to music for the Anglican church remains central to music and worship in many churches today.

The readings are Isaiah 64 vv.9-10 (the Latin text of which Byrd set in his motet Ne irascaris, Domine), and Colossians 3 vv.12-17, in which St Paul encourages his readers to 'sing psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs to God'.

Byrd's music featured includes Ne irascaris Domine, Tribue Domine, the Nunc dimittis from the Second Service, and movements from his three Masses.

Producer: Ben Collingwood.

Last on

More episodes

Previous

Next

Programme Script

Jonathan:Good morning. I’m Jonathan Arnold, and I’m standing in the lovely sunshine outside the Church of St Peter and St Paul, in Stondon Massey, a beautiful Church in rural in Essex. Around me are the graves of parishioners who’ve been buried here over the past 800 years, and among them is thought to be buried one of the greatest ever English composers. William Byrd died on 4th July 1623 (400 years ago), and he spent the last 30 years of his life here writing music for worship, and for his patron Lord Petre at Ingatestone Hall, just a few miles away.

��

As a professional singer and a priest, I have had the privilege of singing Byrd’s music throughout my adult life, and this morning we’re going to explore together how Byrd’s faith and discipleship influenced his glorious music.

��

Music: The Second Service (Nunc dimittis) (Byrd) [Performed by the Choir of Magdalen College, Oxford]

��

Harry Christophers:

Byrd is constantly aware of the text he’s writing, he’s knows his scripture inside out, and he’s making us interpret what he believes in.

��

Katie Bank:

Byrd’s music really captivates the emotional side of what it was like to be in that time, unlike any other composer of his day.

��

David Allinson:

There are moments of true, unshakeable faith revealed in his music, because Byrd is pointing the way for all of us beyond. He really understands the human condition.

��

Kerry McCarthy:

Even in his own lifetime, he was a musician who was loved and honoured among musicians, and that's still very, very much alive today. If you speak to choral singers about Byrd, whether they're professional singers or amateur singers, they will just light up and start talking about their favourite pieces.��

��

Jonathan:

Here inside the Church on the South wall, is a memorial to William Byrd, erected in 1923, giving him the title ‘A Father of Musick’, and today we celebrate his life and his phenomenal contribution to Christian music and worship.

��

He was a genius at using polyphonic music beautifully and expertly to express the meaning of text, whether in his religious sacred music, using verses from scripture, or in secular songs and madrigals. He also left a legacy of keyboard and consort music. He was pre-eminent in expressing his religious feelings through the music.

��

Music: Christ rising (Byrd) [Performed by Alamire]

��

Jonathan:

Lord God, you are worthy of all praise; We thank you for the gift of music to lift our hearts and enhance our worship. May we know what it is to be lost in the wonder of your praise, and come at last to the place where angels and archangels and all the choirs of heaven sing your praise for evermore, in Jesus’ name. Amen.

��

On the wall in the vestry here in the Church of St Peter and St Paul, Stondon Massey is a copy of Byrd’s will.

��

Music: Fantasia a 4 (Byrd) [Performed by the Brisk Recorder Quartet]

��

Byrd (Actor):

��

Jonathan:

Living as a Catholic in a protestant country Byrd had a troubled life and was unpopular with the church authorities here at Stondon Massey. We lament the continuing division amongst Christian denominations today.

��

Lord, we have too often exchanged the worship of the living God for idols of our own imagining. And as we gather to offer our praises to the holy and undivided Trinity, and to worship him in spirit and in truth, forgive us our divisions and disunity and bring us closer to one another and to you in love.

��

Music: Mass for 5 voices (Kyrie) (Byrd) [Performed by the Choir of Westminster Abbey]

��

Jonathan:

May God forgive us when we fail in our understanding, diligence and patience to behold his glory in the world and in our lives and may He draw us closer to Him, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

��

Jonathan:

William Byrd lived through turbulent times in England, witnessing considerable political and religious change. He was born in the reign of Henry VIII, who broke away from Papal authority in Rome, then Byrd lived through the Protestant England of Edward VI, a short return to Catholicism with Mary Tudor, and through the long reign of Elizabeth I and well into the Jacobean period. Living in a Protestant country became dangerous for Catholic families at the time, as Byrd scholar Professor Kerry McCarthy explains.

��

Kerry:

Once it became clear that the Church of England was pretty much settled, things weren't going to go back to the way they had been, was the answer fight or flight? And a lot of people opted for flight, they went into exile, they went to various Catholic parts of Europe where they could practise freely.

��

But for Byrd, I think it fit his temperament much better to stay, and to struggle, and also to help where he could. In fact some of the very first documents in the first person don't have to do with music. They are letters helping out other Catholics who've fallen into various kinds of financial ruin and political disgrace, and here's Mr Byrd giving them a hand. And that's something I think he knew he was in the position to do, and he enjoyed doing, and he didn't shy away from the conflict.

��

Jonathan:

On a number of occasions Byrd was fined for not attending Protestant church services in Stondon Massey, but as conductor and singer Dr David Allinson explains, his employment at the royal court probably enabled Byrd to escape more serious punishment.

��

David:

It’s easy to romanticise him as a sort of exile, a sort of outsider, a member of a persecuted minority group, and also a man whose unshakeable faith brings him into conflict with authority, and I think that’s very appealing. But of course we have to remember that Byrd is also truly an establishment figure; he’s consorting with aristocrats, he’s close to the monarch, and in fact it’s this proximity to power which in part gives him the ability to be a dissident in his own society. But he walks the line, he plays the political game.

��

Jonathan:

Byrd was a pupil of the great composer Thomas Tallis. Their personal and professional relationship was of huge significance for Elizabethan music and, in recognition of this, in 1575 they were given responsibility by the monarch for the importing, printing, publishing, and sale of music and the printing of music paper. Byrd composed an anthem in honour of Elizabeth I, with verses adapted from Psalm 21.

��

Music: O Lord make thy servant Elizabeth (Byrd) [Performed by the Choir of Westminster Abbey]

��

Jonathan:

Byrd is known to have had a profound faith, and music historian Dr Katie Bank – from the University of Birmingham – explains how that religious belief is expressed in his music.

��

Katie:

If you were to think about specific pieces where Byrd’s faith is particularly noticeable it’s actually a very tricky thing to say because you have a piece, for example Civitas Sancti tui which describes the destruction of Jerusalem.

��

Music: Civitas sancti tui (Byrd) [Performed by The Sixteen]

��

Katie:

People have often thought that this was a symbol to describe the plight of the English Catholics in Protestant England. Now when Byrd sets that in a particularly moving way, is that a gesture of faith, is it a gesture of politics, and in many ways these things are inseparable.

��

I personally tend to see Byrd’s faith more in overarching themes, moralizing themes in his music and in his musical approaches, rather than in any specific thing that he does in terms of his text setting. He always chooses really interesting texts, whether he’s writing music for recreational play at home, Latin music for clandestine services, settings for Anglican worship. He remains fundamentally who he is, both as a composer, and – one has to believe – as a person of faith as well. There’s an almost stubborn integrity to the way that he sets texts that I think is very revealing of his faith.

��

Jonathan:

Civitas sancti tui is the second part of one of Byrd’s 1589 ‘Jerusalem motets’, Ne irascaris, Domine. It’s a sombre setting of words from Isaiah 64 (read for us this morning by the vicar of Stondon Massey, The Reverend Samantha Brazier-Gibbs). The words and music focus on the plight of the captives in exile, reflecting Byrd’s own plight as a Catholic living in a Protestant England.

��

Music: Ne irascaris (Byrd) [Performed by The Sixteen]

��

Samantha: Isaiah 64: 9-10

Do not be angry, Lord, beyond measure, do not remember our sins for ever. O look upon us as we pray for we are all your people. Your sacred cities have become a wasteland, even Zion is a wasteland, Jerusalem a desolation.

��

Jonathan:

I’m here in the church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields in London where I’m singing with the Sixteen in their 23rd year of Choral Pilgrimage concerts, which this year focuses on the work of William Byrd and those who influenced him. Harry Christophers is the founder and director of The Sixteen and finds profound longing and deep faith in Byrd’s music.

��

Harry:

It’s so passionately Catholic, and particularly of course in all the Latin music, and bearing in mind this is Latin music written in Protestant England. You’ve got to remember that he was a signed up member of the Chapel Royal; he had made a proclamation that he would follow the faith – the Anglican faith – by being a gentleman of the Chapel Royal, but of course, as we know, he spent his life as a Catholic. We think of pieces like Laudibus in sanctis – very joyful, almost like a sacred madrigal – but then later in life there are pieces like Turn our captivity O Lord, that you really do get the sense actually I’m pleading for sort of remission, I’m pleading to allow myself to worship as I want to worship.

��

Music: Turn our captivity O Lord (Byrd) [Performed by The Sixteen]

��

Jonathan:

Byrd himself believed that the music he wrote came from a divine power, as Katie Bank explains.

��

Katie:

We’re very lucky that we have writing from Byrd in the preface to his 1605 Gradualia about his process of composing.

��

Byrd (Actor):

In the words themselves (as I have learned from experience) there is such obscure and hidden power that to a person thinking about divine things, diligently and earnestly turning them over in his mind, the most appropriate musical phrases come. I know not how, and offer themselves freely to the mind that is not lazy or inert.

��

Katie:

To me this suggests that faith, or at least a sincere contemplation of divine words processed through the human mind is how music is created to Byrd. And in a way this suggests that the divine is the thing that makes the music come, not some special talent that he’s attributing to himself, other than perhaps suggesting he’s definitely not a lazy or inert human!

��

Music: Fantasia for organ (Byrd) [Performed by Davit Moroney]

��

Jonathan:

In 1563 Byrd was appointed as organist at Lincoln Cathedral where he stayed until 1572. Byrd’s successor there is the current director of music, Aric Prentice, who reads our second reading in the Cathedral. It’s from St Paul’s letter to the Colossians.

��

Aric: Reading: Colossians 3: 12-17

As God’s chosen ones, holy and beloved, clothe yourselves with compassion, kindness, humility, meekness, and patience. Bear with one another and, if anyone has a complaint against another, forgive each other; just as the Lord has forgiven you, so you also must forgive. Above all, clothe yourselves with love, which binds everything together in perfect harmony. And let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts, to which indeed you were called in the one body. And be thankful. Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly; teach and admonish one another in all wisdom; and with gratitude in your hearts sing psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs to God. And whatever you do, in word or deed, do everything in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him.

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

Jonathan:

St Paul knew the power of music to express our Christian faith. In this beautiful passage from his letter to the Colossians music is the natural expression of gratitude for the gifts of God and His kingdom values of compassion, kindness, humility, forgiveness, peace, wisdom and above all love. When we encounter the beauty of art, music, and word in the singing of voices, we each begin a journey towards being truly the people God created us to be. To encounter a spiritual community through music is to glimpse something of the divine spark.

��

This journey into the mystery of humanity and divinity was expressed to me in a conversation with the singer and former Tallis Scholar, Francis Steele, who told me how, for him, William Byrd’s motet Tribue Domine has the power to reveal divine mysteries. He said:

��

‘It’s a motet whose text deals both with the mundane, the fragility of humanity, and the numinous, the omnipotence and nature of the Trinity. Byrd’s music articulated that text just as a great actor would his lines. Singing that piece seemed to bring me as close to the mystery of the Trinity as I shall ever approach.’

��

Music: Tribue Domine (Byrd) [Performed by Alamire]

��

The words, music and meaning of Byrd’s Tribue Domine, paradoxically take us beyond both words and reason. It is a magisterial work in three parts with words taken from a medieval text once attributed to St Augustine of Hippo:

��

‘Grant, O Lord, that while I am placed in this feeble body my heart shall praise Thee, my tongue shall praise thee, and all my bones shall say: Lord, who is like unto Thee? Thou art God Almighty, Who as three persons in one.

I entreat, pray and request Thee, increase my faith, increase my hope, increase

my charity.

Glory to the highest and undivided Trinity, whose works are inseparable, whose

reign remains without end.’

��

This piece exemplifies the importance of the triune God for Byrd’s life, faith, and music. The fervour of the words are lifted through the glorious music, creating an art form that meets a deep and intrinsic human need for the spiritual, mystical, and transcendent.

��

To engage with religious texts through music is to touch the numinous – that is the unknowable, inexpressible divine – and to somehow satisfy the need for the spiritual in all of us.

��

Byrd’s music demands time and space to listen, engage and be transformed by it. It offers us an art form which comprises a presence of spirituality which draws the individual away from self and back into a relationship with community; away from selfish desire towards a sacrificial relationship with others that leads towards the chief subject of all artistic and natural beauty, which is love and, ultimately, God.

��

Just as St Paul exhorted the Colossians to sing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, so we continue to do today, in churches, cathedrals and concert halls, nourishing those who believe and reaching out to those on the fringes of faith, who find something transformational in the musical language. Music can lead people to consider the most profound aspects of human life and lead them to the threshold of the divine. Music is a bridge between the secular and the sacred, between humanity and divinity, between earth and heaven.

��

Music: Pavane and Galliard ‘Sir William Petre’ (Byrd) [Performed by Sophie Yates]

��

Jonathan:

I’m here at Ingatestone Hall, with which Byrd had a very close connection, and with its owner, Lord Petre. And I’m here with the current Lord Petre, John.

��

Lord Petre:

The first John Petre (subsequently first Lord Petre), his principle residence was actually at Thorndon Hall, and William Byrd, we know from various accounts and inventories, would visit him at Thorndon Hall frequently. But we also know that he came here at Ingatestone Hall because it was the custom for the family to spend their Christmases here. And in particular we know a bit more about the Christmas of 1590, when on Boxing Day the saddler was sent to London to bring Mr Byrd down to Ingatestone Hall, where there were already five musicians, also brought from London, to ‘play upon the violins’, and brackets had been set up in the Great Hall to carry the double virginals. What Byrd did while he was here we don’t know, all we know is he accompanied the saddler back to London after twelfth night, but I hope that he might have at least performed the last Pavan and Galliard in the My Layde Nevells Book Collection, which was written about that time, and was dedicated to John’s teenage son, William.

��

Jonathan:

And Byrd and Lord Petre had close connections through their shared religious feelings as well, didn’t they?

��

Lord Petre:

Absolutely so. In fact the connection between them was in two respects: first of all their mutual interest in music; but yes, you’re right, they were both also avowed Roman Catholics – how they managed to get away with it at that time, that is a very complicated story. So when William Byrd visited he would have not only supervised the secular musical celebration but also there would have been sacred music as well.

��

Jonathan:

And of course here is where Byrd’s beautiful settings of the Mass – for three voices, four voices, and five voices – three settings, would have been performed in private worship.

��

Lord Petre:

Almost certainly that’s the case. Obviously we have nothing written down about that because that’s the point, it was all secret.

��

Music: Mass for Four Voices (Agnus Dei) {performed by Stile Antico]

��

Jonathan:

Harry Christophers again.

��

Harry:

If we look at the three masses, these were all written for private devotion, for singing around a table, mass in private, recusant Catholics, so incredibly powerful, very simple, but oh my goodness, incredibly emotional. If we think of the Agnus Dei from the Four Part Mass I can’t really think of a more emotional, intensely emotional piece than that. He’s making sure that what he writes is very much his music making, his voice coming through, he’s challenging the singers to make the most of it and to work out a way how to sing it, and how to inject into the way he’s written what he means through the text. And for me, I think that stands out really from a lot of other composers of the English Renaissance.

��

Jonathan:

It’s known that the Petre family sheltered Jesuit Catholic priests at Ingatestone Hall in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, during Byrd’s lifetime. Two secret hideaways – known as priest holes – were built into the walls of the house to conceal altar ware and sacred books. The priests themselves would often hide in plain sight, pretending to be members of the household, and more often than not would evade capture from the authorities who would make regular inspections.

��

David Allinson believes that Byrd’s connection with Jesuits almost certainly influenced the composer’s music.

��

David:

I think his attitude to sacred texts is probably shaped a great deal by his interaction with Jesuits, and this Ignatian idea that you almost imbibe each phrase of text and dwell upon its deeper meanings. It’s like an inward meditation. It’s just that of course that Byrd doesn’t allow that thought to stay as an introverted inside thought, he then gives breath to that phrase in the form of polyphony. And what I find as a conductor is that he can be immensely generous in the way he unfolds emotion, but he can also be very flinty – almost harsh – sometimes in creating textures which are unyielding and tough, which confront suffering, which articulate sorrow and rage. And also, of course, the flip side is he can be immensely consoling. And I find, above all, a sort of unshakeable faith is imbedded at the heart of his writing.

��

Music: Civitas sancti tui (Byrd, arr, Nico Muhly) [Performed by Aurora Orchestra]

��

Jonathan:

I’m standing beside one of the priests’ hiding places here at Ingatestone Hall for our prayers today.

��

In the quietness,

And aware that we are only part of a great multitude,

on earth and in heaven,

who share in the Church’s offering of worship,

let us join ourselves with them

and bring to God in prayer our own hopes and needs,

together with those of all his children.

��

For the leaders of the churches,

for all who share Christ's ministry,

and especially for those who order the worship of your people,

that many may draw close to you in prayer and praise.

Let us pray to the Lord.

��

For all whom you inspire to compose music,

for all to whom you give skill and devotion to perform it,

and for all your children who are enriched and renewed by it.

Let us pray to the Lord.

��

For all who have gone before us in the faith of Christ,

for those who in past generations have enriched your Church with fine music,

and for all who have served as musicians.

Let us pray to the Lord.

��

As our Saviour has taught us, so we pray.

��

Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name; thy kingdom come; thy will be done;

on earth as it is in heaven. Give us today our daily bread. And forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation; but deliver us from evil. For thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory for ever and ever. Amen.

��

Music: Ave verum (Byrd) [Performed by the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge]

��

Jonathan:

Whatever one’s religious or faith persuasion, there is no doubt that William Byrd’s music is as powerful today as it has ever been. It is sung in churches of different denominations, drawing Christians together in prayer and praise, as well as appealing to a huge range of people beyond the church. One piece which has endured in popularity is the beautiful motet Ave Verum, Hail, True Body, often sung as Holy Communion is taken. It is a miniature masterpiece that reminds us of our unity in Christ.

Broadcast

- Sun 9 Jul 2023 08:10�������� Radio 4