It鈥檚 easier to get vox pops for a mobile journalist than a film crew, new research shows

Panu Karhunen

Reuters Institute, University of Oxford

"If it'd been a big camera, I probably wouldn't have stopped here at all," the 72-year-old woman told me.

We were in the middle of a shopping centre in Helsinki, Finland. The woman was participating in an experiment as part of my .

I was trying to find out who gets more vox pop interviews: a mobile journalist working alone and filming on a smartphone or a two-person film crew using a conventional broadcast camera. As I'll explain, the 72-year-old was far from being the only one to prefer mobile journalism over the traditional TV film crew.

The mobile journalist and the TV crew each approached 200 people.

The field experiment was conducted in the Kamppi shopping centre in February. Altogether, 400 passers-by were approached. The mobile journalist worked alone using a smartphone, a handle grip, an attached microphone and an external lens. The two-person crew worked with a professional broadcast camera, a tripod and a reporter microphone.

The approaches were carried out as follows:

1. The subjects were people passing the interview spot.

2. The reporter tried to make eye contact with a potential participant. He moved at most three metres from the interview spot to do so.

3. The reporter said: "May I ask a question?"

4. If the participant stopped, the reporter said: "We are doing vox pop interviews about holidays for Ilta-Sanomat. What is the best way to spend a holiday?" (Ilta-Sanomat is the largest news media in Finland. We had company's permission to use the newspaper's name in the field experiment.)

5. After the participant had answered the question, the reporter revealed that he was not doing an interview for Ilta-Sanomat and that he was doing research for the Oxford University's Reuters Institute.

Here’s what happened:

Video copyright Panu Karhunen, used with kind permission

People may be more willing to stop and answer questions at certain times of day so we tried to make the conditions as equal as possible: on the first day the TV crew approached 100 people in the morning, and the mobile journalist approached 100 people in the afternoon. The next day we reversed that pattern.

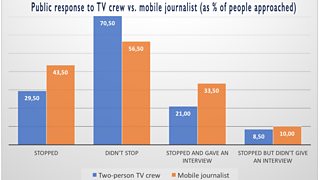

And so, the results:

Mobile journalist: 34% gave an interview

TV crew: 21% gave an interview

Or in more detail:

Some of the participants were asked which interviewing method they preferred.

"I prefer this (mobile journalism). It doesn't feel so scary when there's only one person and one camera... If I compare it to a situation with two persons and another one would be with the camera there." (37-year old woman)

"I don't know. This was the first time I gave an interview. Maybe I'd prefer to speak one on one, because it feels friendlier. Maybe. And more personal," (26-year-old man)

There were differences in the results based on gender. Women were more inclined to participate in both cases: 39% gave an interview to the mobile journalist and 25% to the TV crew. (For men: 27% for mobile journalist; 16% for TV crew.)

Age matters too. The sample was divided into those aged 40 and above and those younger than that. While mobile journalism was a more effective method for obtaining interviews in both groups, the difference between the methods was greater among the younger group:

YOUNGER GROUP:

Mobile journalist: 40%

TV crew: 23%

(Difference of 17%)

OLDER GROUP:

Mobile journalist: 27%

TV crew: 19%

(Difference of 8%)

(However, when the sample is split into smaller groups the margin of error and possibility of statistical bias grow.)

In conclusion, mobile journalism seems to be an efficient way to get vox pop interviews – although I would not claim that these results would necessarily apply to every kind of interview and every context. Finns are keen on using smartphones. Perhaps the citizens of the old Nokia country are used to filming more videos on their smartphones than people in countries with lower smartphone use.

It would be interesting to see whether smartphone penetration or media culture affects the results.

However, one serious disadvantage emerged from responses to the mobile journalist in the experiment: lack of credibility.

"A proper camera is more convincing. Anybody can shoot with a phone. You don't know that it's real if it's just a phone. " (26-year-old woman)

Preconceptions of mobile journalists are likely to change when the method becomes more common. Before that, as Dutch mobile journalist Wytse Vellinga said in the research interview, mobile journalists should simply explain more clearly what they are doing.

Notes: Percentages are rounded to the nearest integer. The margin of error in the comparison between mobile and TV crew was 6.93% with a confidence level of 95%.

is available on the Reuters Institute's website.