New media in a new Tajikistan

Esfandiar Adena

Head of �������� Bureau in Dushanbe, Tajikistan

Tagged with:

Esfandiar Adena is the �������� Media Action Fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) for spring 2013. In April, he will begin a research project at RISJ in Oxford on social media and governance in Tajikistan.

I was born in 1975 in a remote village in Tajikistan called Vashan. It lies high up in the northern Zarafshan valley which has historically been so isolated that even dialects differ from one village to another. But that isolation is beginning to change.��

��

The village of Vashan, northern Tajikistan.

As a child, I remember one occasion when my father fell ill with high blood pressure. My brother had to go to the central office of our Soviet-style collective farm to even find a phone and it took at least two hours for the ambulance to arrive to take my father to the clinic 8km away. Patients, including pregnant women, sometimes died on the way to the clinic. ��

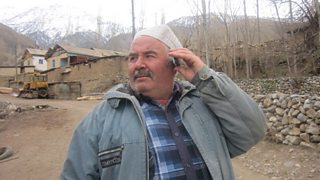

Now mobile phones have revolutionised the lives of those villagers. Telavmorad Ayev, the schoolteacher who taught me the Persian alphabet all those years ago, told me, "Thank God that such a device was invented. When someone becomes ill, we can now easily call doctors, who can give advice and guidance right away so it's not necessary sometimes to even visit patients. So much energy, time and effort is saved." ��

Schoolteacher Telavmorad Ayev in Vashan.

Phones, but no electricity

But it's not all good news. "During the Soviet period we had abundant electricity but no phones. Now we have mobiles but no electricity," says Mehroddin Nabiyev, who owns a small grocery shop in the village and uses his mobile to call partners in other villages. "It is such an interesting but painful contrast." ��

Mehroddin’s shop in Vashan.

The Foreign Factor

It's this huge part of the Tajikistan population working abroad that has had a lasting impact on mobile communication in the country.

Faced with widespread corruption, poverty and unemployment in Tajikistan, more than one million Tajiks have left the country for work over the past two decades, mainly for the construction sites in Russia and Kazakhstan. Abuse and harassment of these foreign migrants is common, but the money they send home amounts to roughly 47% of Tajikistan’s national GDP.

Having a mobile in Tajikistan therefore isn't just about entertainment. It’s a vital way for migrant workers to regularly call their relatives and send money. ��

Vashan's mobile transmitter.

And it's one of the main factors explaining why mobile communication is far more advanced than any other economic sector, such as energy, agriculture or transport, in Tajikistan.�� LTE (Long-Term Evolution, the new 4G wireless broadband standard) technologies and VoIP (internet telephony) are widespread. What's more, 3.7 million people – almost half of the population – use the internet and according to statistics, the majority of these internet users are young people using mobiles phone to go online.

Online debate - and the political backlash

This rapid growth in mobile usage among young populations has provided a new space for young Tajik people to actively discuss social, religious, economic and political problems in a country where more than 40% of the population live below the poverty line.

"Young people are very interested in social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Russian-made Odnoklasniki (Classmates)," Asamidin Atayev, the head of the Association of Internet Providers of Tajikistan says. "They make new friends, chat, comment and debate in social forums. They upload their photos, videos and share views and news."

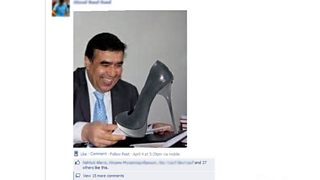

A Facebook posting mocking former Tajik Education Minister Abdujabbar Rahmanov.

Young people are actively challenging their leaders on such online platforms. In Facebook groups with names as Tajikistan Online, Platforma, Tajikistan-e Nouvin (New Tajikistan), people are posting and sharing caricatures of government officials. Most recently, a caricature of former Education Minister Abdujabbar Rahmanov appeared on Facebook after he ordered female students to wear shoes with heels not less than 10 cm.

This increased use of social media has not gone unnoticed. The authorities’ response has been furious: there have been several attempts to block access to Facebook, for example, although such attempts have only made social networks more popular.

Even Tajikistan's President, Emamali Rahman, has gone on record to criticise the Tajiks’ growing use of mobile phones. In a televised speech in January 2009, he said that money spent on mobile phones is money "spent ineffectively" and that "only two mobile phones are enough in a family. If people save their money, we would be able to build new power stations." The state television channel also took mobile companies' adverts off air and started to broadcast programmes about the health risks of mobile phones.

President Rahman has recently celebrated his 20th year in power but the signs are that his popularity is decreasing and that this year’s presidential election in November will prove a great challenge to his remaining in office. New media technologies – embodied by the mobile phone in people’s pockets – will surely play an interesting role in these elections.

The �������� Media Action fellowship at The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism is funded by the Global Grant from the UK Government's Department forInternational Development.

Related links