Cross-cultural questionnaire design: A journey without end

Chuanyan Zhu

Research Officer

Tagged with:

�������� Media Action's Climate Asia survey visits a family in Indonesia.

I've been working for �������� Media Action for eight weeks. In my first week, I started work on the Climate Asia survey which is taking place across seven countries with a combined population of 3.4 billion people.

Before I knew it, these surveys were being piloted in four Asian countries: Bangladesh, Indonesia, India and Pakistan. As information started to feed back to the team in London, I became immersed in detail. Questionnaire design across this many countries is shaped by multiple, and sometimes surprising, cultural differences.

One of the things we want to understand through the Climate Asia project is whether people are likely to change their behaviour to respond to changes in food availability.

One question we asked people is whether they might 'eat less meat' or 'not increase meat consumption'. Confusion around language was immediately noticeable. Our country researcher from Indonesia explained that 'meat' actually only means red meat but not chicken or fish.

And for me, a Chinese woman living in the UK, eating less meat is an action I would take to deal with the increase of food prices or to keep fit. However, for the people in some countries in Asia, it means something different. "Eating and serving meat is considered a sign of upward social mobility," Khadija Zaheer, our researcher in Pakistan, told us. "People cannot afford to eat meat so why would they be thinking of reducing it?"

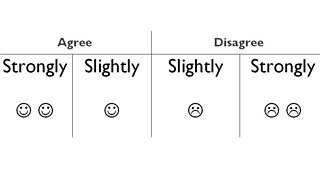

Asking people to use a scale, from say from 1 to 5, to quantify how they feel about an issue is well understood in many countries. But in Bangladesh, Pakistan and India, it took a lot of time to do this, particularly in rural areas. So we simplified the process to a two-step prompt, first asking respondents to choose between 'agree' and 'disagree' and then to choose between 'strongly (dis)agree' and 'slightly (dis)agree'. This way, by simply adapting our approach, we were still able to get people to use the degree of scale we wanted.

Of course nothing is ever simple when it comes to working across seven very different countries. China and Indonesia, for instance, decided they didn’t need this distinction. Why people in one country are happy to make one choice in five, while people in other countries are not is still a mystery to me.

On the other hand some concepts are particularly hard to explain with words so pictures and illustrations have been introduced to explain the concepts and scales. Smiling – or frowning – faces can be used, for example, to capture whether people strongly or slightly agree or disagree.

Show card with smiling and frowning faces.

At the end of our pilot for the survey, nearly 300 pieces of feedback had been recorded. This deeply shaped the questionnaires we used in the formal field work. Suggestions on language, translation, scales, tools, and many more reminded me of how important it is to understand the individual cultural contexts, language, and communication habits in cross-cultural research.

Related links

Elsewhere on �������� Media Action: