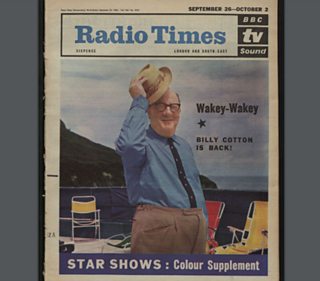

For nearly 40 years, Billy Cotton was a star of �������� Radio and Television - here Radio Times celebrates another series of his television shows in 1964

The Billy Cotton Band Show was one of the greatest popular music shows on the �������� from the late 1940s through to the late 1960s, and bandleader Billy Cotton was one of the ��������'s most colourful personalities.

Unusually, it ran on both radio, and then in a TV version from 1956. Billy Cotton was a star of radio from the 1930s and stayed in the limelight until his untimely death in 1969.

He was born into a large family in Smith Square, Westminster in 1899. As a boy he sang in a choir and played drums and bugle in the Boy Scouts. He enlisted in the army during the First World War after lying about his age, and saw action at Gallipoli. He later joined the Royal Flying Corps and qualified as a pilot with the RAF in its earliest days.

After the war he had a number of jobs but wanted a career in music, joining his nephew Laurie Johnson’s band as a drummer (coming from a large family, Cotton was of a similar age). He started his own orchestra, the London Savannah Band, in 1925 at the height of the Jazz Age.

As the band evolved through the 20s and 30s, becoming known simply as the Billy Cotton Band, their style developed with comedy turns, although the main emphasis was still playing for dancing in ballrooms and night clubs. With their signature tune Somebody Stole My Gal, the band increased steadily in popularity and soon had a thriving recording career.

Their came in 1930 when they had a residency at Ciro’s Night Club. They regularly appeared in their own right until the outbreak of war, with guest spots including some early editions of in 1939.

As war broke out Cotton was keen to offer his services to his country, imagining he would be in the thick of things as in the previous conflict. His eyesight precluded him from operational flying, and he was asked to reassemble his band to perform with ENSA (Entertainment National Service Association) which provided shows for the troops.

The band travelled to France during the ‘Phoney War’, but was able to make its way home before being caught up in the German Bltizkrieg of May 1940. Regular broadcasts of the band continued, including appearances on wartime shows and .

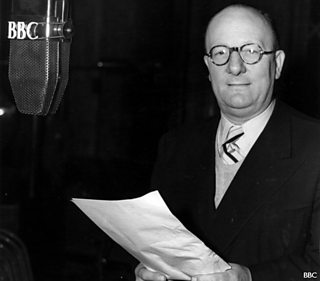

An early shot of Billy Cotton, for once without his band. Don't ask us why but we think he's in a �������� studio...

Cotton’s style was his own: no outstanding musician, his role as a drummer was abandoned very early on in favour of leading the band and shaping its musical policy. He also emerged as a personality, with a taste for rough, bluff cockney humour. He combined this with strict discipline and a paternalistic approach to leading the band. He could be a hard man to please but he respected talent and admired professionalism.

He was an unashamed populist, given to greeting any musical innovation with comments like ‘they wouldn’t understand that in Wigan’. He was a great encourager of new talent and a genuine team player, even if he was undisputedly the captain of the team.

After the war, while the programmes continued, in 1949 it was decided to introduce a new format. The new show would go out at 10.30 on Sunday mornings, which fitted in more easily with the band’s touring schedule. After a few weeks, a title was settled on which would become very familiar to the British public over the next 20 years: .

Because the programmes went out at such an early hour, Cotton once came into the rehearsal room to find his band half asleep, and gave a shout of “Wakey Wakey!” – which would become his trademark introduction to all his future shows, and the .

There was some controversy over the placing of the programme as it was felt as it was going out at a time when church services were on, it might prove a too-attractive alternative – a far cry from the sober �������� schedules on pre-war Sundays where there was a blanket ban on popular entertainment.

Vicars would sometimes alter the times of their services to avoid the clash, as the show proved to be so popular, but in September 1950 the programme shifted to 1.30pm, and would become a part of the Sunday lunchtime ritual for many families for years to come.

Cotton also made variety of other appearances including a series called with Tessie O’Shea, broadcast from a theatre, and in 1951 was the subject of an edition of the dramatised documentary series . He was fast becoming a well-loved radio personality.

But television was another matter. He had largely shied away from the medium, feeling that its technical demands outweighed any advantage that might be gained from appearing, and before the advent of ITV in 1955 the fees were extremely small by his terms. His first credit is for in 1953, but his band’s next major TV outing would be on an early ITV series.

However, this was not a happy experience, and he soon arranged a meeting with the ��������’s head of television light entertainment, Ronnie Waldman. Waldman offered a joint radio and television deal, and Cotton agreed to the contract being exclusive. Asked to name his price, Cotton made some calculations and wrote a figure on a napkin, which Waldman agreed to at once. In the manner of the times, Cotton and his band’s �������� contracts were gentlemen’s agreements – purely on a handshake.

Rehearsing the Billy Cotton Band Show - BC and Cliff we all recognise, but who is the dapper gent on the left? Impress us with your knowledge...

The television version of was launched on 29 March 1956. This was by way of a pilot, and the next episode did not go out until 22 May, but then a series followed with fortnightly episodes, allowing the band to continue touring.

The television shows were carefully crafted by producer Brian Tesler. Although given to fooling around and using comedy in his stage and radio shows, Cotton was reluctant to take centre stage on television, and it took some persuading before he could be convinced to join in with dance numbers by the Leslie Roberts Silhouettes, a troupe specially assembled for the series.

They got their name from the use of an electronic process called inlay – superimposing images when they were shot in shadow against a light backdrop. These techniques were used in a bid to wow viewers and fend off ITV’s competition.

A regular musical guest who became very popular was the pianist , and later on the cheerful was also to appear frequently. Other guests included comedians like Tommy Cooper and Harry Secombe, as well as Ted Rogers, who made his name on the show, and new pop singers such as Adam Faith and Cliff Richard.

Christmas 1956 saw Cotton firmly established as a television star, and he was cast as Alderman Fitzwarren, with the late Sylvia Peters as his daughter Alice, in , which featured a large supporting cast of �������� personalities in cameos. In 1957 there was also a new producer for the Band Show, Cotton’s son, Bill Jnr, who had left a career in music publishing, and would in time become a high-ranking �������� executive, ending up as Managing Director of Television.

In 1958 a new format was brought to the show, coming from the supposed ‘’, though this usually alternated with the regular Band Show. At Christmas that year the Band Show provided one of the segments of the first , a concoction of mini-episodes of comedy and variety shows which would become a semi-regular feature of seasonal celebrations until 1972.

Two days later there was a special episode, and in February 1959 the series celebrated its 50th edition. The same year saw Cotton given the award for outstanding services to British popular music at the .

One 1961 edition featured Hollywood legend . Though surrounded by an entourage of minders and writers, even Hope had to wait for Cotton to finish his preparations before being attended to – and recognised that Cotton was the boss on the show.

By autumn 1962 the ostensible boss, Bill Cotton Jnr, had left the programme as his �������� career progressed, and he was replaced by Johnnie Stewart, and soon after that by Michael Hurll who had begun as a lowly floor assistant on the show, and who would remain as producer for the rest of its run. Cotton meanwhile was voted Show Business Personality for 1962 by the .

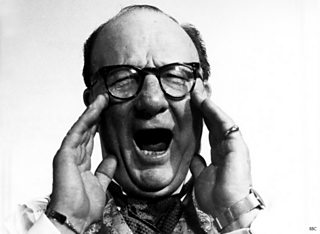

Wakey-Wakey! Each edition of the Billy Cotton Band Show began with the catchphrase, often introduced in a novel comedy skit

Though the show continued to feature favourite old songs, groups like and The Seekers began to make guest appearances as the musical landscape moved on, along with pop stars like Dusty Springfield, Cilla Black and .

But it was time for another tweak to the format, and in autumn 1965 the television show was renamed . There was a greater emphasis on guest acts, and a tighter format, but the Band was as much a part of proceedings as ever, and the renowned Tiller Girls now provided the dancing.

The of the show went out in November 1966 from the Talk of the Town night club by Leicester Square. By pacing the shows, which went out either fortnightly or monthly at various times, and had long breaks between series, there seemed no reason why the programme could not go on forever.

The next series of Music-Hall began in the middle of the following year, and a further series followed in 1968, moving from the limited facilities of the �������� Television Theatre to the more spacious . The shows were mostly live, though Cotton was determinedly a family entertainer so there was no risk of bad language or risqué material.

The last episode of Billy Cotton’s Music-Hall went out on , with guests Moira Anderson, Ronnie Corbett and Jack Douglas. Cotton made two more television appearances, a Show of the Week called , which was on ��������2, and thus his only colour television programme, and a cameo on his friend Cilla Black’s New Year’s Eve show on ��������1. The last radio series of the Billy Cotton Band Show had ended in October.

Cotton was a big man in many ways – including his girth. He had an active early life but a stressful later one, constantly worrying about the quality of his shows and looking after the band. After a stroke in the early 60s he soon returned to work and didn’t make allowances for his failing health. In March 1969, he had just finished writing his autobiography, when he died suddenly while watching a boxing match at Wembley. He was 69. Two months later the �������� screened , a tribute from his friends and colleagues, on what would have been his 70th birthday.

Billy Cotton was a man of many parts, a showman of the old school who believed in giving the public what they wanted. He was unique, yet down-to-earth, a dedicated professional without ever being slick. They don’t make them like that any more.

We'd love to hear your memories of the Billy Cotton Band Show, on radio or television. Use the space below to comment on this, or other programmes you've investigated using the Genome website.