Elsie and Doris Waters - famous as comedy duo Gert and Daisy - compete in a Spelling Bee in 1944

Alan Connor is a journalist, TV presenter and author of several books on quizzes. He has also found some insights in the �������� Genome listings into the origins of the game.

While doing the peculiar job of "question editor", in between deciding on the questions that contestants and viewers will answer, I have come up with some questions for myself. Inevitably, I suppose. Questions about questions.

And the answers aren't obvious at first. Why on earth do we quiz? When did we start doing so? What makes a good – and, indeed, a rotten – quiz question? And why don't quiz shows give sandwich toasters as prizes any more?

I'd imagined that to find how and why Britain began to make a game out of asking and answering questions, I'd be going back to Victorian parlours... or perhaps deeper into history: to Enlightenment thinkers outsmarting each other over a cup of new-fangled coffee after a hard day's enlightening.

As would curtly respond to any of these guesses: nope. The answers were, in fact, to be found in the ��������'s searchable archive of Radio Times listings, Genome. It was the �������� that got Britain addicted to the quiz. Genome was, as I expected, an absolute treasure trove: but you can't find the earliest quizzes by using "quiz" as a search term. The first quizzes were not even called "quizzes". They were bees.

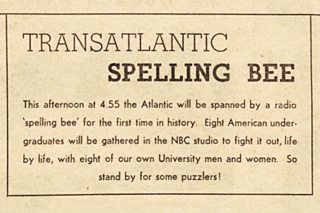

A Transatlantic Spelling Bee listing from 1938

That word comes from the US; so too did the ��������'s first "Bee": on 30 January 1938, the Regional Programme London broadcast , a "spelling match between members of Harvard and Radcliffe Colleges, and Oxford University". Radio Times took pains to explain to listeners what we now take for granted as part of a contest of knowledge, reassuring them that the programme was "an extension of an idea that has been very popular with American listeners". In other words: don't panic, this idea of people competing to answer questions might just prove entertaining.

After a few more Spelling Bees, an unnamed, unsung pioneer at Regional Programme Northern twigged that the same set-up – microphones, buzzers, questions – could be used in a competition based on something other than spelling. And so it was that Britain got its first proper quiz: April 1938's , a "contest across the Pennines between schoolchildren of both counties".

Quizzes were, I believe, radio's first genuine innovation. Other programmes took something that already existed – the newspaper, the concert, the lecture – and made it into programming. But the quiz was a beast of broadcasting.

It already existed in US radio, but right from that first trans-Pennine event, British quiz programmes were a very different activity to their cocky US cousin. Cash prizes? Certainly not! Oily hosts? The thought never crossed the Corporation's minds.

The atmosphere was wholesome, improving and very much borrowed from the classroom – a tradition which continued through Top of the Form (from 1948, " between teams representing boys' schools in London"), University Challenge, Blockbusters and the rest. (And then there was , where a panel answered questions such as "What is happiness?" and "Are thoughts things or about things?" Answers not provided below.)

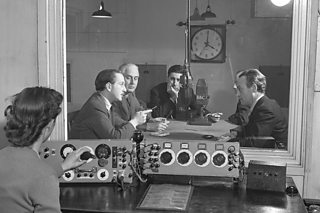

Leon Shepley, Geoffrey Dennis, Anthony Lawrence, John Marus and Ruggero Orlando recording a 1949 episode of The Brains Trust

Before all that, though, the quiz had to establish itself as part of broadcasting furniture. It took a war.

During World War Two, the "bee" was put to work as part of the national effort. No question-setter of that era was ever stuck thinking "what shall I ask them about this time?"; the answer was: whatever will be more likely to bring us victory. And the rewards came in the form of being better informed: the �������� Service offered its Training Bee, where teams gathered at a Warden's Post to be tested on the finer points of firefighting. You found out whether you were digging correctly for victory on the (subtitled "What Land Girls ought to know") and the Forces Programme kept the troops on their toes with its regular ("a quiz bee with teams from all ranks").

There was also a one-off called : Sons in France against Parents in England brought soldiers back into contact with their nearest and dearest. But it was a one-off for good reason: The poignancy of this on-air family reunion was slightly undermined by the audible vomiting of one of the inebriated Sons and the ��������’s concern that his equally jolly brothers-in-arms seemed constantly on the verge of giving away their location to the Germans.

University Challenge presenter Jeremy Paxman appearing on Parkinson in 2002

Those programmes are long gone, but two of the biggest of the quiz programmes of today have their origins in World War Two. was once a form of on-base entertainment for US soldiers. The starters and bonuses had different names, because University Challenge is actually based on a basketball metaphor: answer a "jump ball" (starter-for-ten) and you got a chance at three "free throws" (bonuses). Intriguing enough for GIs, and the quiz, as Jeremy Paxman slyly notes in his book on the programme, was really "a way to keep servicemen from their more conventional styles of recreation".

The success of University Challenge (originally broadcast by ITV) spurred the �������� to come up with something to match. The producer tasked with this, Bill Wright, had been a flight-sergeant during the war, but was shot down and kept in solitary confinement for three weeks and prisoner-of-war camps for three years.

He was plagued with nightmares in which an interrogator insisted, in the dark, for his name, rank and serial number while he sat in a black chair under a bright light.

One morning, though, he announced to his wife that he was going to keep the chair and make it the central point of a new quiz, with a spin on "name, rank, serial number" before the first question. No prizes for of that one, whose Genome listing announces: "This new and exciting brain game invites contenders to take the stand and defend their claim to the title".

Magnus Magnusson hosted Mastermind for 25 years.

Yes, the �������� might eventually have succumbed to the occasional excitement of modest money prizes and shiny floors, but British quiz's wartime edifying roots can still be seen, and we remain the only country to broadcast, in prime-time, quizzes with little to no reward, where the viewer feels gratified if they've answered as many as one or two of the questions. Good. We don't care about prizes.

Over at iPlayer, there's collection of vintage quizzes curated by Richard Osman, which include the programme that Bill Wright came up with before Mastermind, the extraordinary .