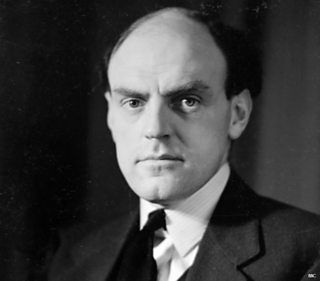

John Charles Walsham Reith, later Sir John, then 1st Baron Reith of Stonehaven, 1889-1971

It’s common knowledge that the ��������’s first Director General was Lord Reith… except that, as so often with common knowledge, that’s not quite the full story. John Reith was appointed General Manager of the British Broadcasting Company in December 1922, a month after it started broadcasting, and became Director General of the British Broadcasting Corporation on its inauguration on 1 January 1927.

John Charles Walsham Reith was born in 1889, the youngest by ten years of seven siblings. His father was a minister with the Free Church of Scotland, which gave him a strong religious foundation in life. Reith was a very tall young man, at six feet six, and an imposing physical presence was matched by his assertive manner.

He attended Glasgow Technical College prior to an apprenticeship with a railway manufacturing company; a fellow student was , whose path would cross Reith’s again in the future.

When war broke out in 1914, Reith, who was in the , was put in charge of a transport unit in France. In 1915, he was wounded in the face by a German sniper’s bullet, and the scar made his already forbidding face all the more striking.

Reith was sent to America to liaise with factories producing rifles for the British army – this being before the United States joined the war. He greatly improved productivity, and saw the progress the Americans had made in mass production. Reith also found himself in demand as a speaker, and he saw a possible future in politics. When the Americans joined the war in 1917, their munitions factories were required for their own army, and he returned home.

In October 1922, he saw an advertisement in the Morning Post newspaper, inviting applications for the General Managership of a new concern called the British Broadcasting Company. Despite having no idea what broadcasting was (few did at that time), Reith applied.

Reith did not get an immediate reply, but in early December was interviewed by Sir William Noble, chairman of the Broadcasting Committee, and offered the job (the identities of the five other candidates are unknown). began at the �������� on 30 December 1922, six weeks after the first official broadcast by the �������� on November 14.

Sir John Reith locks the door of Savoy Hill for the last time in May 1932, as the �������� moves to Broadcasting House

The station, call sign 2LO, had begun transmitting experimentally in May that year. Though licensed by the government and answerable to the Post Master General, the �������� was a private company, a consortium of six large electrical equipment manufacturers, with some representation of smaller concerns.

There were immediately numerous problems on Reith’s desk to be solved. News was the jealously guarded preserve of the newspapers, and their trade association did not want sales affected by radio bulletins. Eventually it was agreed that no news could be broadcast before 7pm, and the news agencies who provided content had to be acknowledged on each bulletin. It was not until the late 1930s that the �������� was allowed to collect news itself.

One early trial for the �������� was the General Strike of May 1926, which affected most industries, including newspapers. The �������� however was able to go on, and broadcasting of news at any time of the day was allowed for the duration of the 9-day strike.

The �������� was already in the throes of a major government enquiry about the future of broadcasting. It was decided to turn the Company into the British Broadcasting Corporation, with a Royal Charter to set out its aims and responsibilities. Reith had already been promoted from to Managing Director in 1923; now he became Director General of the public corporation, and he gained a knighthood to boot.

One innovation with the Corporation was a Board of Governors, to ensure the �������� followed its remit. While the precise role and influence of the Governors later proved a point of contention, Sir John had his own problems in the early days. Used to being left to get on with things by the old Company board, he found the new Governors keener on scrutinising his activities.

After several years of experimentation with short wave transmission, the was launched in 1932, and later evolved into the Overseas Service and then the . At Christmas 1932, the was broadcast for the first time throughout the Empire.

The ��������’s expanding staff and operations saw it rehoused twice in Reith’s time. Its original offices were in the GEC building on Kingsway, and when it outgrew these, new premises were found in the Institute of Electrical Engineers on Savoy Hill. Even here space was limited, and a purpose-built headquarters, Broadcasting House, was opened in May 1932.

London was not of course the be-all and end-all of the �������� even in its founding years, in fact for some time it was difficult to network programmes, and each region created much of its own output. Gradually more and more was shared, and in 1930 �������� sound services were re-organised. With the availability of more transmitters, the was established for the whole country, with a complementary for each sub-section of the UK.

Reith however was not a great fan of ‘the provinces’ even though he was brought up in Glasgow, and was reluctant to allow too much independence. Throughout his life, especially once he left the ��������, he constantly criticised what he saw as the falling standards of the Corporation.

�������� Television prepares to cover the 1937 Coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth from Apsley Gate, Hyde Park

One area of broadcasting Reith was never entirely reconciled to was television. Television was first demonstrated to the press by Reith’s old college fellow, John Logie Baird, in 1926. For the next few years Baird lobbied for access to transmitters, but was frustrated as the �������� had the monopoly of broadcasting, and its engineers were unconvinced of the potential of his primitive 30-line mechanical system.

In 1929 the �������� gave in, and began. Programmes came from Baird’s own studio, as there was no room in the Savoy Hill for the cumbersome equipment. In 1932 the �������� started producing programmes themselves, with space found in the newly opened Broadcasting House. In February 1934 television was moved out to 16 Portland Place.

The low-definition service ended in , by which time higher definition technology had been developed both by Baird (240 lines) and by the rival Marconi-EMI consortium (405 lines). The new service began officially in November 1936, though a scratch programme was thrown together in August for the RadiOlympia exhibition, and experimental tests began in October, both from Alexandra Palace.

The official was staged on both systems consecutively, after which Baird and Marconi-EMI were used on alternate weeks until February 1937, when the Baird system was dropped. Reith had stormed out of the opening ceremony, unimpressed. To be fair, it was a while before television was much to write home about, but he didn’t give it much of a chance. Although little survives of pre-war television apart from a few , there is a sound recording of the opening ceremony.

One of the last big challenges Reith faced as Director General came in 1936 with the of Edward VIII. Although all mention of it was kept out of British media, people in the higher echelons of society knew of the affair between the Prince of Wales and a married American, Wallis Simpson.

After he succeeded to the throne in January 1936, Edward eventually decided he would marry Mrs Simpson, and give up the Crown, realising he could not have both. Reith supervised the broadcast to the nation on 10 December 1936, as the now Prince Edward (later the Duke of Windsor) announced that he was unable to continue as King ‘without the help and support of the woman I love’.

Edward’s brother Albert, became King instead, as George VI, and in May 1937 the �������� covered its first Coronation. Even television was involved, in the first proper outside broadcast, covering part of the at Hyde Park Corner.

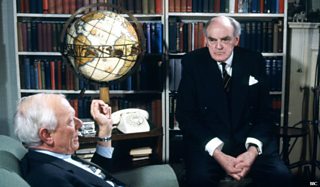

Malcolm Muggeridge interviews Reith for Lord Reith Looks Back, 1967 - a meeting of minds?

Sir John Reith left the �������� on the last day of June 1938 take over the ailing Imperial Airways, fore-runner of British Airways. However he found himself with little to do at the outbreak of World War Two in 1939, since civil aviation effectively ceased. He was eventually appointed Minister of Information in Neville Chamberlain’ government, and became MP for Southampton in an unopposed by-election. But soon after, Winston Churchill became Prime Minister.

According to biographers, including Ian McIntyre in (1993), Churchill and Reith did not get on – they clashed during the General Strike, and during the 30s when Churchill wanted to broadcast against giving more autonomy to India, he thought Reith had vetoed it. Reith found himself reshuffled into less appealing posts, and he was sent to the House of Lords, as Baron Reith of Stonehaven (after his birthplace).

In 1942, Lord Reith found himself out of the government altogether, and he spent the rest of the war in the Royal Navy, making behind-the-scenes contributions to the plans for the D-Day invasion. He kept attending the House of Lords, and contributed to debates about the setting up of ITV in the 1950s, being passionately against it – even if the �������� was not what it had been in his time, he would still rather it had kept its monopoly.

His relations with later Directors General of the �������� were sometimes difficult, even when they went out of their way to befriend him, like , DG from 1944 to 1952. He had ambitions to return as Chairman of the �������� Governors, but that post always passed him by. He was a constant critic of the ��������’s policies for years afterwards, even railing against the start of the Third Programme, seeing it as putting serious music and talks into a ghetto where they would not reach the masses.

Reith relented in his opposition to television on two occasions, by submitting to John Freeman’s questions in in 1960, and in a three-part interview with Malcolm Muggeridge, , in 1967. Reith used the latter to discourse at length about his life and especially his time at the ��������, and pronounced his opinion that television was a ‘social menace’.

Reith died on 16 June 1971, just short of his 82nd birthday. His funeral was private, but there was a suitably grand memorial service on 22 July. Lord Reith, whose name has passed into the language as a byword for a particular set of broadcasting standards, was already a historical figure for his effective founding of the ��������.

If he was disappointed by the course of his later life, his legacy is assured – if nothing else, apart from the prestigious , the ��������’s internal computer network is named after him, which means that at least on two levels, Lord Reith can never be forgotten by the organisation he shaped…

You can read more about Lord Reith’s life in Asa Briggs’ The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom (volumes I & II), in his own autobiography Into the Wind, his published diaries, and biographies by Ian McIntyre, Andrew Boyle and others.