The television mast on Alexandra Palace was erected in 1936. During World War 2 it was used to send out fake homing signals to German bombers, but in February/March 1947 it was out of action when television was closed down to conserve fuel

It now seems like an incredible tale from the dim and distant past, but because of a national fuel shortage during the harsh winter of early 1947, the �������� Television Service and the Third Programme, precursor to Radio 3, closed down for several weeks to conserve electricity.

Today’s Sunday Post looks at the changes to the planned schedules at this time. Another notable aspect of the crisis was that for two weeks, Radio Times was not printed, so listings of what did go out are missing from the database – and some of the programmes billed were not actually transmitted.

During the war, there was a constant need to economise on fuel, including to maintain the electricity supply that was vital for armament production. encouraged people to save fuel, because other than coal and gas produced at home, all other fuel was imported by sea, and the danger of U-Boat attacks meant it was vital not to waste resources.

Post-war, conditions actually worsened in Britain in many ways. There was no longer the same danger to shipping, but the British economy had suffered greatly. The country was almost bankrupt from the cost of fighting the war, and its infrastructure took years to .

Fuel shortages

There was increasing concern about fuel shortages by the autumn of 1946. A �������� memo in November that year talked about the electricity authorities' anxiety about the coming winter. Defence priorities during the war meant that worn out electricity generating machinery had not been replaced, and work on this now required some plant to be taken out of service. Power cuts were anticipated especially if the winter was severe, which turned out to be the case.

By the second month of the new year, the situation was getting critical. A memo of 8 February from the DG’s office proposed that the Light and Third programmes could close down each day at 11 pm, with the �������� Service closing, after the news, three minutes later. Evening television would continue, but the morning , and afternoon programmes, would cease. The memo also noted that electricity cuts might result in certain �������� studios or outside broadcasts being left without power, so contingency plans were put in place for this possibility.

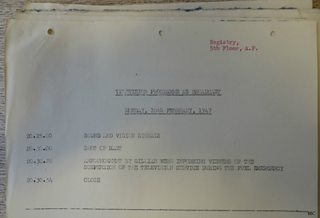

The fateful �������� document recording the closedown of the television service

In the event, this was not quite how things happened: both the Third and television were shut down completely for some time. Television programmes continued as normal until , with the usual announcement of the programmes scheduled for the next day, followed by the sound-only news, and closedown.

However, the following day, Monday 10 February, there were no transmissions until 8.25pm, when the usual tuning signals and identifying shot of the Alexandra Palace mast was followed by an announcement (by , one of a number of contract announcers in early post-war television) that the service would be suspended during the emergency. At 8.30pm and 54 seconds, the service closed again.

Nothing on the box...

For a few days the �������� paperwork faithfully reports "no transmission" on the television service, until that too was abandoned on 18 February with the note "no transmission until further notice". For once, �������� officialdom’s obsession with recording what has happened, even if nothing had actually happened, ran out of steam.

The other minority service, the , also ceased during the crisis. On 10 February a memo advised that it would close down following an announcement at 6pm that evening, although some programmes scheduled during the suspension period could be recorded for later transmission, in order to honour �������� contracts – although in the case of talks, only if the speaker would be unavailable when the emergency was expected to be over in two to three weeks' time.

It gradually dawns on Edmundo Ros and his band that the �������� Television Service has closed down and they are wasting their time...

In the event, the Third Programme only remained off the air until 26 February. This might look like favouritism, as television took far longer to return, but both production and consumption of television used far more power than radio. Also, the Third Programme was available nationwide, while television was confined to the south east of England within range of the Alexandra Palace transmitter, and sets were expensive – so the potential audience affected was much smaller.

However radio overall played its part in the economy drive. Additional savings were achieved by amalgamating the �������� Service and Light Programme schedules from 15 February to 15 March, although just during the day; the evening schedules retained separate services. Radio Times printed when it resumed publication on 7 March, but with a box-out showing a combined schedule in case the restrictions had not been lifted.

On Tuesday , television returned. After the tuning signals and the filmed shot of the television mast, accompanied by Eric Coates’ Television March (this being the earliest de facto television ident), broadcasting resumed with a production of the play Outward Bound, postponed from exactly a month before. Even then the gremlins stepped in – there was a breakdown after 5 minutes and the play, after a brief return, did not start again fully until 8.54pm. Gillian Webb was again the announcer.

Here comes Muffin

Although the service was back, for a while programmes were confined to the evenings only. After a week, the morning transmission of the demonstration film, Television is Here Again recommenced. Afternoon programmes returned at weekends only from 22 March, including live sport and children’s programmes like .

Radio Times too was affected by the fuel shortage. As will be apparent from studying the Genome listings, and as is described in the , there were two weeks in which Radio Times did not appear, the editions which would have been published on 21 and 28 February.

For this reason, Genome is not just missing the television and Third Programme listings in Genome, as they were not transmitted, but also the �������� Service and Light Programme billings, as there was no magazine to take them from. As with other occasions when there is no Radio Times, it is intended eventually to add these from �������� records.

Television in fact did not even return exactly when Radio Times said it would, though the magazine admitted that it might not: programme pages for the first two editions after the magazine resumed warned that programmes were liable to change if circumstances demanded. In fact, though television listings appear for , it was another two days before any programmes were actually broadcast.

The planned 1947 outside broadcast of busmen's training at Chiswick depot was delayed until 1949 - which is about average where buses are concerned

So what programmes did listeners and viewers miss out on while the Third Programme and Television were suspended?

Highlights on the Third Programme included Sound on the Air, a studio discussion about "the relation between the actual sounds made in the studio and those that the listener is likely to hear" (ironically, given that they didn't hear anything in the event); , a drama written and produced by the poet (and �������� producer) Louis MacNeice, based on an ancient Greek story by Apuleis; and Aristophanes’s The Frogs, given consecutively in translation and then in the original Greek – along with the customary diet of "serious" music.

Television programmes cancelled or postponed ranged from Forecast of Fashion, plays like the repertory staple Outward Bound (as mentioned above), outside broadcasts from Chiswick showing and the , some ballet, and the international between England and France.

Normal service resumed

Full �������� programmes were finally restored by the end of April. There were further fuel scares in 1950 and 1951 (and rationing of coal would continue until 1958), but in the event there were no further interruptions or restrictions to broadcasting – at least not until the 1970s. In 1972-74, disputes in the mining industry resulted in the three-day week, power cuts, and curtailed hours of broadcasting to save power, but no actual closure of services.