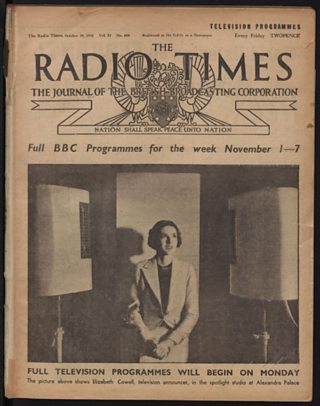

Announcer Elizabeth Cowell is Radio Times' cover star for the launch of high definition television on 2 November 1936. 'Full television programmes' consisted of an hour in the afternoon and an hour in the evening

We don't want to make a habit of debunking (or at the very least, clarifying) myths, but as the �������� are celebrating the 80th anniversary of the first television broadcast, we might as well point out that it’s not as simple as that. Sorry.

It's certainly true that on , the �������� launched the world's first high definition television service, from its studios at Alexandra Palace in North London.

However, as we have discussed in this blog before, �������� transmitters had been used to relay television since , and the �������� had been making programmes themselves since . Moreover, when the switch was made from the low definition 30-line standard to what was then called high definition, the first programmes were actually transmitted two months earlier than the date usually commemorated, at the end of August 1936.

Those programmes were very much a scratch service, as the newly appointed television staff had little over a week to prepare, when the �������� was asked to provide television for the exhibition. Its organisers were having trouble selling stands to exhibitors and needed an attractive gimmick to gain publicity, and the �������� obliged.

Given that there was so little time, the programmes, which were not billed in Radio Times, were necessarily simple. Unlike subsequent years when there was a �������� Television studio at itself, in 1936, there was no outside broadcast equipment yet in service, so all the programmes came direct from Alexandra Palace.

Miss Helen McKay performs 'Here's Looking at You' for the RadiOlympia audience, backed by the �������� Television Orchestra.

Compared to the regular programmes that started later, there was a high proportion of film in these experimental shows: indeed the first item broadcast, on 26 August 1936, was a Paul Rotha documentary film, Cover to Cover.

This was followed by the first proper live programme, with singer Helen McKay. This was interrupted by a technical fault (as the start of the transmission had also been). It was followed by an excerpt from the feature film First a Girl, then another outing for Miss McKay preceded a longer programme of film excerpts, including Charles Laughton in Rembrandt, and Paul Robeson in Showboat.

And that, lasting a little over one and three-quarters hours including tuning signals and breakdowns, was the first day of high-definition television.

That day the Baird system was used, with its still-meagre 240-line image. When the Selsdon Committee decreed in January 1935 that the �������� should experimentally conduct high-definition television, it said both the two systems then available should have the chance to prove their worth. One was that developed by John Logie Baird's company from his 30-line low definition system, which was mechanical. The other had been developed by the Marconi-EMI consortium and electronic.

The Baird system had two separate ways of capturing pictures: close-ups came from the 'spotlight' studio, in which artists were shut in a darkened cubicle, lit by infra-red, so reading from a script was out of the question, and cueing them to perform was problematic. Long shots used the 'intermediate film' system, where scenes were shot on a film camera using 17.5 mm stock (35mm film cut in two). There was a complex system to rapidly process and scan it, to turn it into a television picture.

While this all took only a few seconds to achieve, it made cueing items in the 'spotlight' studio even harder. The delay did however allow performers to see themselves on screen, which in the days of live television was a rare thing. Electronic cameras designed by the American pioneer were also used by Baird later on, but despite adaptation they too were less than perfect.

The Baird system required special make-up to accentuate artists' features - as recreated in Jack Rosenthal's 1986 play The Fools on the Hill, with Anthony Calf as Leslie Mitchell and Maev Alexander as Jasmine Bligh

It had been decided to alternate the Baird and Marconi-EMI systems daily during the RadiOlympia broadcasts, so the latter 405-line system was used on the second day. This saw the first exterior shot, of Alexandra Park in which the Palace stood, showing that the Marconi-EMI system could handle daylight, and also was physically flexible. The cameras were mounted on tripods or wheeled dollies, and could move about relatively freely in the studio – the Baird cameras were static.

The same films were shown as the previous day, and they would be repeated every day until the end of RadiOlympia – with occasional additions, including . These would continue until the closedown of the service in 1939, providing the only visual news programmes of the 1930s. Post-war, the �������� would start its own , which evolved into the modern �������� News.

27 August also saw the first variety programme, called Here’s Looking at You, with Helen McKay joined by singing group The Three Admirals, comedy 'horse' act The Griffiths Brothers and Miss Lutie, and the Creole singers/dancers Carol Chilton and Maceo Thomas. While Miss McKay had just been accompanied by a pianist, Henry Bronkhurst, the day before, this day saw the debut of the , a specially created group under the baton of Hyam Greenbaum.

Here's Looking at You would be repeated on the remaining Marconi-EMI days only, as the Baird system was not equal to its production requirements. Baird days had simpler items, some featuring artists from the programme in solo spots.

The RadiOlympia shows ended on 5 September with another innovation – again on a Marconi-EMI day – the first actual outside broadcast. This was just a matter of taking a camera to the main entrance of Alexandra Palace to show comedian emerging with Gerald Cock, the Director of Television. The service finally shut down at seven minutes past two in the afternoon.

The construction of the television mast at Alexandra Palace. Ally Pally was used by the �������� until 1954 for general programmes, then for news bulletins and colour tests, and finally for Open University programmes until 1981.

Following this rough-and-ready start, the television staff resumed their preparations for the scheduled launch on 2 November. In fact, they were back making programmes on 1 October, when a series of test transmissions began.

The first person to appear in these was , one of the three announcers recruited after extensive auditions earlier in the year. This was her first appearance on television, as both she and colleague Elizabeth Cowell had been indisposed and unable to join chief announcer for the first broadcasts. Cowell appeared with Mitchell after a few days, before which he was helped out by �������� veteran Cecil Lewis, one of the production staff.

Announcers then were somewhat different to the modern equivalent, and were in effect hosts for each transmission, appearing in vision, introducing and often taking part in programmes.

The morning test sessions were given over to the showing of films, such as the documentary Droitwich (telling the story of the ��������’s state-of-the-art transmitter), and , John Grierson and Stuart’s Legg's film about the �������� as a whole. When the service started properly, there were no transmissions in the morning until the summer of 1937, when demonstration films were shown.

Afternoon programmes were a dry run for the official service, and the daily alternation of Baird and Marconi-EMI became a week-about rotation. There were no evening programmes in the test period, and as with the RadiOlympia shows, there were no transmissions on Sundays – these only started in April 1938.

On the first day of Marconi-EMI tests on 5 October, excerpts from the play The Two Bouquets by Eleanor and Herbert Farjeon became the first drama to be shown on high-definition television. There had been a few dramas on the low-definition service, necessarily unambitious due to its limitations, the first being Pirandello's in 1930.

The Two Bouquets was not an original script for television, nor an original production – it was a version of a play running at the Ambassadors Theatre. For many years it would be unusual for any drama to be written specially for television.

Contributors and crew for the first edition of Picture Page, October 1936. Note Joan Miller's fake switchboard, the title caption at the back, and how a message can become garbled, as with the veteran suffragette's placard on the left...

Other test programmes included more outside broadcasts from the Alexandra Palace grounds, an appearance by , variety shows, with their mix of singers, dancers and speciality acts (the dancers in one edition were Delfont and Toko, the former of whom would become the agent and impresario Bernard Delfont) - and the first edition of the great television hit of the 30s – Picture Page.

Picture Page was centred around Canadian actress , sitting at a fake telephone switchboard where she ‘connected’ viewers to each item on the programme. Most of the interviews were conducted by Leslie Mitchell, and included a wide variety of people, from celebrities to members of the general public with interesting occupations or hobbies. Guests in the first edition included a prizewinning Siamese cat and 'poster model' Dinah Sheridan, later a successful actress.

There were still technical problems to be ironed out, and not just with the Baird system – the Marconi-EMI transmission on the afternoon of 20 October was cancelled when the vision transmitter failed. The Baird days were capable of innovation, as on 26 October when the first weather forecast was shown, explained by H. Corless of the Met Office. They would continue in the , before being rested until their return in .

Test programmes ended on 28 October, the last show being Dress Parade, with five 'mannequins' (models) wearing the latest fashions. Five days later, television began in earnest.

Adele Dixon in the opening day's variety show (Marconi-EMI version). The cameraman is peering round his Emitron camera to frame his shot because the first models had no viewfinder

On Monday 2 November 1936, at two minutes past three, Jasmine Bligh and Leslie Mitchell introduced the . As with the RadiOlympia and the test transmissions, the Baird system was used first (history/legend has it that this was decided by the toss of a coin; the result was to everyone’s dismay except Baird’s).

The programme was short (it was thought people’s attention would lapse after fifteen minutes), with speeches by , the �������� Chairman, Major Tryon M.P., the Postmaster General, Lord Selsdon, chair of the Television Advisory Committee, and Sir Harry Greer of the Baird Company.

The notable omissions were Baird himself, and the �������� Director General, Sir John Reith, who left in high dudgeon, and was never convinced of the merits of television.

After a (shorter than advertised, but featuring Adèle Dixon singing the new composition ‘Television’) and music from the Television Orchestra, the whole transmission was repeated at 4pm on Marconi-EMI, with Alfred Clark from the company replacing Sir Harry Greer in the opening ceremony. As with Baird, there was no place for Isaac Schoenberg, who headed Marconi-EMI’s research team and is another contender for the title of the ‘inventor’ of television.

Transmissions reverted to the Baird system for the rest of the week. The evening programme comprised the film , another edition of , a and the first ‘recorded’ item – footage from the Baird intermediate film system of Lord Selsdon’s speech earlier in the day. Television was underway.

However the Baird system’s days were numbered, being cumbersome and more susceptible to technical breakdown. Its last transmission was on . The burning down of the in December 1936, where Baird had his , meant that work on improving his system was fatally set back. Though he continued working on television, including colour and high definition (in the modern sense of 1000 lines or more), Baird died, almost forgotten, on 14 June 1946.

Seven days earlier the �������� Television Service had after the Second World War, using the Marconi-EMI system, and introduced by Jasmine Bligh. Apart from a brief closedown when fuel stocks were low the following winter, it has never gone away...

Celebrations of the 80th anniversary of television continue on the �������� with a on ��������4 on 2 November, recreating the opening night of the world's first regular high-definition television service. And see for how Radio Times previewed the forthcoming television service in October 1936.

A clip from Television Comes to London