Using storytelling to make statistics accessible

Mahmuda Hoque

Research Officer, ÷˜≤•¥Û–„ Media Action (Bangladesh)

Tagged with:

Bangladesh-based researcher Mahmuda Hoque explains how her team created a story about “Maya”, a 19-year-old mother, to help bring their findings about antenatal preparations to life.

Researchers often uncover insights with real practical relevance but then struggle to communicate their findings compellingly to those who can make use of them.

I came up against this predicament myself when my team here in Bangladesh surveyed 3,000 mothers, 2,000 fathers and 2,000 mothers-in-law as part of a study about maternal, newborn and child health. One of the aims of our study was to explore which factors helped pregnant women prepare sufficiently – and feel sufficiently prepared – for the birth of their child. The findings would go on to inform the .

We found that knowing what precautionary steps to take ahead of giving birth was the most important factor. The next most significant factor was discussing the issues with family and friends, followed by living in a society where it was common for families to prepare for birth, having a positive attitude and believing in one’s ability to take action.

We wanted to share our results with the project and production team as it was important for them to understand the driving forces behind birth preparedness and their relative importance. But we were worried that they wouldn’t really engage with what we’d discovered.

Bringing numbers to life

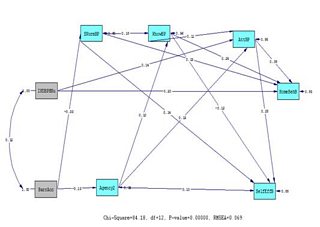

You see, we’d reached our findings using structural equation modelling (SEM), which encompasses a series of statistical methods. SEM involves creating a model of how you think factors, such as knowledge and social norms, influence behaviour and then testing it with real-life data. The SEM model is rather off-putting to a layperson due to its complexity, associated jargon (regression analysis, factor analysis, simultaneous equation modeling) and all of the lines and numbers needed to draw it out. Take a look:

Not easy for a non-statistician to understand…

We spent hours and hours puzzling over how to tell our non-statistician colleagues about the results in a way that would resonate with them. Finally, we realised that the best way of communicating our findings to our project and production team trying to create a dramatic story was to tell them a story!

To write this story of birth preparedness, we drew not only on our model but also on our existing in-depth qualitative research, to help develop our characters and set the scene.

Telling Maya’s story

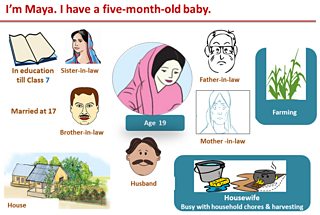

"Maya", our protagonist, represents the ideal expectant mother ahead of a home birth. She’s knowledgeable about how to prepare for the arrival of her baby, confident that she can act accordingly and knows that her social circle will support her decisions. But she also knows other women who aren't as prepared because of the obstacles they face.

An abridged version of Maya’s story is narrated below, along with notes (in italics) on the findings underpinning each part of the storyline.

As is the case with many women in Bangladesh, Maya married young and moved to live with her husband and his family in their village.

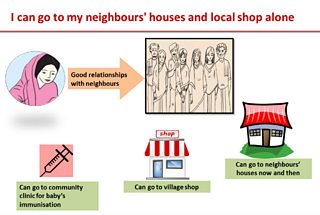

We told the story of how – after moving to her husband’s village – Maya developed good relationships with her neighbours. She's able to move around the village freely and this helps her feel more confident and positive about her ability to prepare for the birth of her baby.

Finding: When women have agency, they can move around more freely, which makes them more positive that they'll be ready for the arrival of a baby, which in turn makes them more likely to actually be prepared.

But Maya also found that there were some married women who were not allowed to go outside or talk to non-family members without their husband’s or in-laws’ permission.

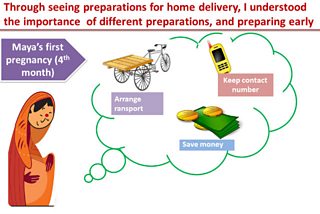

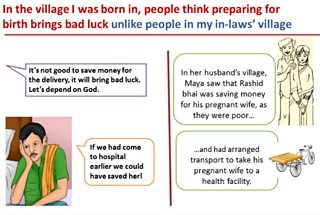

Gradually, Maya discovered that it was the norm in her husband’s village for pregnant women’s families – rich and poor alike – to prepare for delivery day by saving money, pre-arranging transport and collecting emergency contact numbers.

This contrasted with the practice in the village where she was born and brought up, where preparing for a birth was bad luck. Yet Maya seized on the knowledge that preparation at an early stage could save a pregnant woman’s life in case of difficulties.

Finding: knowledge is the key factor in determining whether mothers are prepared but how they prepare is also influenced by what they think everyone else is doing – social norms are important.

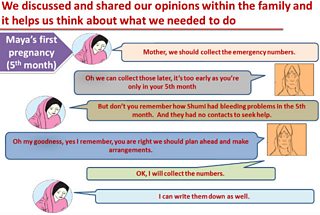

Good relationships with her husband and in-laws ensured Maya was confident to involve them in her planning. Her mother-in-law initially thought getting ready in the first trimester was too early but Maya managed to win her round by discussing what could go wrong if they delayed.

Finding: talking about getting ready for a baby arriving with friends and family is the second most important factor in determining whether mothers are prepared.

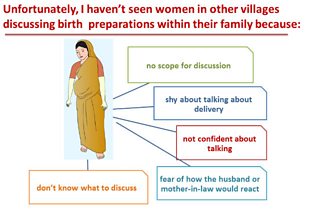

However, many women have no hope of having such discussions due to shyness, a lack of awareness or belief in their ability to take action.

Fortunately, Maya has a safe delivery at home, having done all the necessary preparation.

Finding: Being knowledgeable about birth preparation, able to discuss it, living among others taking similar precautions and feeling confident about taking action are the most important factors in determining whether a mother is ready for giving birth.

How was our story received?

Our non-statistician colleagues really appreciated having the findings presented through one woman’s life journey and recognised the factors behind birth preparedness from their own experiences. Production colleagues said that the presentation helped them plot out a storyline. It really helped them to portray the role of ‘discussion’; conversations got more screentime in the drama and took place between families at home and out in the community, rather than just between health workers and pregnant women.

It’s true that statisticians speak a very different language from most people. But the findings of their work are ultimately not so removed from people’s everyday experiences as they might first appear. Storytelling is one effective way of helping people see that.

Related content:

Blog:

Blog:

Blog: