By Chris Hewson, Senior Research Ecologist at BTO

The sound of the British countryside has changed since we lost . Its rich song has disappeared from woodland and scrub, and without discovering why and taking appropriate action, we could lose the species altogether. Recent work at BTO has focused on estimating the population size here in the UK so that important sites can be identified, and unravelling what happens on the species’ migration.

Nightingales feed on insects, especially beetles and ants. Photo by Edmund Fellowes.

Population Estimates

It’s not easy to estimate the size of an entire population of birds. However, having a good understanding of how many individuals are present is vital for conservation efforts, and our was key in the designation of Chattenden Woods and Lodge Hill SSSI and the subsequent to protect its Nightingale habitat. The data we are accessible for other organisations to use, and the methods are described in .

To come to our estimates, we relied on the work of 1,281 volunteers, who surveyed for Nightingales across 2,356 tetrads – and always around the very early hours of dawn, soon after the birds arrived back from their migration. This way, the chances are highest of hearing freshly-arrived male birds sing whilst they compete for territories. The BTO’s team of analysts then used advanced and, in some cases, novel statistical methods to estimate the number of nightingales and uncertainty around it.

The final results showed us a series of 12 estimates, based on different statistical models. These estimates ranged between 5,094 and 5,938 singing male Nightingales. The true size of the population likely lies somewhere between these two values, giving us an idea of how big a local population must be to be nationally important at the widely-used threshold of 1% of the national population. Work is now underway to analyse data on the number of males that remain unpaired. We can then estimate the size of the breeding population, rather than simply the number of territorial males. Any variation in this across the UK range, or with habitat and local Nightingale density, could give us insights into the reasons of decline.

Tracking Nightingales

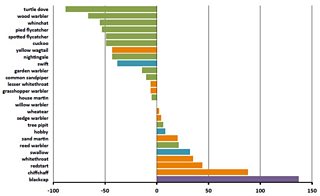

It’s a story of decline for many species that migrate to Sub-Saharan Africa, especially those that winter in the humid parts of West and Central Africa. We are losing not only Nightingales, but also species like and . Tracking where these birds go gives us valuable insights into what could be causing their decline.

Figures of decline; what is happening to the migrants? Data from Ockenden et al (2012)

We’ve been tracking Nightingales since 2009, initially in collaboration with the Swiss Ornithological Institute. we can reconstruct the birds migration path based on light-level recordings, often with surprising accuracy. showed us where they go; a path that takes them via a stopover in Portugal, over the western edge of the Sahara, before ending in Senegambia. Some birds move further later in the winter, taking them to destinations ranging from Guinea Bissau to Liberia. They return in spring along a similar route.

Migration route of a bird tagged in 2012, on its southward route (orange) and northward route (green).

Comparing these data with tracking studies from other countries reveals that the spatial relationships of the breeding populations are maintained in winter – in other words, birds breeding further east also winter further east. This pattern is known as strong migratory connectivity and has implications for how populations respond to environmental changes, as well as the extent to which they interact with each other. To fully understand how clustered our birds are and how they move around in winter, we have started tracking the birds with miniature archival GPS tags. These give us locations 10,000 times more accurate than geolocators (to around 15m instead of 150km), and so will give us far more detail about how the birds spend their lives throughout their annual cycle.

The culture of the Nightingale

The public has shown their care for the Nightingale through their interactions with us, and their generous support to our . More recently, we are seeing that a whole new way of interacting with these enigmatic birds has started to take people on more personal journeys. Award-winning folk singer Sam Lee, working with The Nest Collective has, for example, taken audiences into the countryside on their breeding sites. Through this, audiences are able to share in an immersive and improvised experience, experiencing what happens when bird and human virtuosi come together in musical collaboration. Such approaches reawaken our connection with the Nightingale. Understanding of the cultural associations of the Nightingale is also enabling BTO to take its research to new audiences, broadening our reach and garnering new support whilst strengthening the public’s engagement with the species. Ultimately, we hope this will help to facilitate the research and conservation action that is required in the future to secure it as a British bird.

To learn more about BTO’s current work on Nightingales and Cuckoos, visit .