By James Pearce-Higgins, Director of Science, British Trust for Ornithology

The issue of climate change is in the news on an almost daily basis. We are seeing growing evidence of its impacts on the natural world, from the bleaching of corals in the Indian Ocean, to raging wildfires in Australia, to shrinking ice-sheets affecting polar bears in the Arctic. Closer to home, the fingerprints of climate change are all over the British countryside, but here, the impacts on species are not always negative.

On a dark January morning, the long hot days of summer seem a world away. But in less than three months, thousands of birdwatchers will be getting up early to take part in an annual monitoring scheme run by the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) in partnership with the RSPB and JNCC. By spending just two early mornings counting birds in a specific 1km square, they contribute to national monitoring that has tracked changes in the abundance of breeding bird populations across Britain for over fifty years. Not only does this information tell us which species are increasing or declining, and therefore play an important role in setting conservation priorities, it has also provided vital evidence about the impacts that climate change has had on British birds.

That impact is large. In a last summer, BTO showed that over a third of breeding bird species have been affected by changes in temperature or rainfall over the last 50 years. The strongest effects were during the winter months. Mild winters, such as this year’s, are relatively benign for our resident bird species.

Many birds survive better than they would during a prolonged cold-snap.

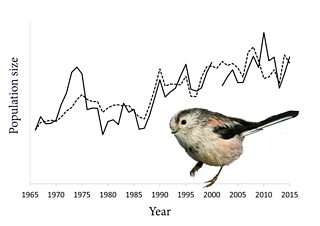

As our winters have warmed in response to climate change, populations of bird species living in the UK have increased over time. Small songbirds that feed on insects like goldcrests, long-tailed tits and wrens have particularly benefitted from warmer weather. In other words, the impacts of climate change are just as apparent in our gardens and across the British countryside as they are in the Arctic or in coral reefs. Our birds are physically adapted to the climate they are in. Wrens in northern Scotland are than those in the south-west of England, which enables them to cope with colder winters compared to their soft English cousins! Whether this will make them able to respond quickly to the changes that they face, time will tell.

Warmer winter temperatures predict that long-tailed tit populations have doubled since the 1960s (dashed line), which match the observed changes (solid line) pretty well.

Not good news for long distance migrants

In contrast, our long-distance migrants, such as willow warblers and cuckoos, are not in Britain during the winter, and so do not benefit from the improved conditions. Populations of many of these species have not increased; in fact, many have declined. Although they are vulnerable to changes in the amount of rain in Africa, where they winter, and to conditions in Europe during migration, the precise reason for these long-term declines is still unclear, which we at BTO are working hard to understand.

Long-distance migrants, such as this Whitethroat, don鈥檛 just face a changing climate in the UK, but also in Africa where they winter. Photo by Edmund Fellowes / BTO.

The results of our research suggest that climate change will continue to alter the balance of bird species in the countryside around us. Whilst this may be to the benefit of many of our familiar resident garden birds, it is unlikely to have the same positive impact on long-distance migrants. Some of our rarer specialists which need a particular kind of habitat to survive are especially vulnerable to climate change. Birds such as golden plovers and black grouse in the uplands, or seabirds like kittiwakes and puffins, face a warming ecosystem where their main prey are less abundant. Whatever the future holds, by helping to monitor bird populations, whether by taking part in the or telling us about the birds that you see all year round through , you can help us understand the changes that are occurring, and help inform what can be done as a result.