The Great British Hedgerow Survey

People's Trust for Endangered Species (PTES)

Partner organisation of the Watches

By Megan Gimber, Key Habitats Project Officer at PTES

Help conservationists fill the gap in hedgerow knowledge this autumn

As we approach the winter months, hedgerow shrubs go to sleep; the leaves fall and the sap retreats to roots. Hedgehogs may be hibernating in drifts of leaves sheltered in the bottom of your hedge; insects both as adults sheltered in nooks, leaf litter or old hollow stalks and as eggs weathering the storms on a leaf; dormice too, if you have particularly impressive hedgerows, may be snoring away waiting for the first flush of spring.

But still hedgerows are alive with birds flitting around collecting the nutritious jewels of hawthorn berries and rose hips, sheltering from the elements and braving our winter for an early crack at spring.

Over-trimmed hawthorn hedgerows, trimmed to the same level each year now losing vegetation at the base, starting to get characteristic mushroom shape, and gappy. Credit E Marnham

However, not everywhere and not every hedge. Any hedge trimmed in autumn loses the wealth of food that historically earned them the role of ‘winter wildlife larder’.

Hedges without hedgerow trees lack the range of opportunities for wildlife that those with a plentiful supply of trees can offer. Over half the priority species using hedgerows are dependent on, or makes use of, hedgerow trees. And any hedge trimmed to the same height year in year out - ignoring their inherent need to grow and change - becomes leggy and can’t provide the vegetation at the base needed by so many.

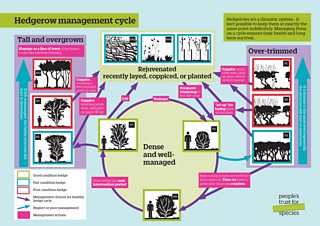

If you look closely, it’s obvious that our hedgerows are living systems. So to keep them healthy, they need to be managed flexibly, taking account of their lifecycle. To attempt to keep a hedge at any one size or point in its lifecycle indefinitely will inevitably cause their structural decline and eventually gappiness and outright loss.

For parts of their lifecycle a hedge can happily be maintained through trimming. In fact sensitive trimming can be what keeps a hedge a hedge. But there’s a limit to this management before rejuvenation is then required, and there are ways in which we can approach trimming to reduce the impact this has on wildlife. Trimming every other year, rather than every year, allows for blossom and fruit. Trimming in late winter, not in autumn, allows them to regain their ‘larder’ status. If they are allowed to increase their size every time they’re trimmed, a bigger, better and more complex habitat develops. And eventually, as they outgrow their allocated space, or as they out-shade the vital vegetation at their base, they’re rejuvenated (through laying or perhaps coppicing), keeping their lifecycle turning.

The hedgerow management cycle. Credit PTES

At this time of year the structures of hedgerows are on display, revealing how our management practices affect them - so now’s a good time to look!

A recently laid hedge hawthorn. Credit Megan Gimber

Then come spring, when the leaves return, it may be time to give our hedgerows a health check. In recent years the outright loss of the hedgerow network has slowed almost to a halt. But we can’t take for granted those we have left. We must work to make sure our remaining hedges are the best they can be.

That’s why People’s Trust for Endangered Species (PTES) has launched a new national survey, . It’s a simple survey to do, and it automatically calculates how healthy a hedgerow is, with scores for the structure, the wildlife and the connectivity value of each.

Added to this, any landowner that takes part receives comprehensive management advice, based on the hedge lifecycle, which can help restore any hedge to a healthy condition.

The data collected from this survey helps us gain a better picture of the health of our hedgerows at a national scale, which in turns help us with our challenge of safeguarding the future of this important habitat.

A dense, well-managed hedgerow with trees. Credit Megan Gimber

So whether you are a landowner, a farmer, part of a wildlife group or just interested in the hedgerows of your parish; this survey is for you. By taking part, you’ll learn how healthy your hedges are, what management will benefit them and also contribute valuable information to a national dataset that will inform conservation decisions in the future.

And although we’re coming to this from a wildlife perspective, there’s certainly value in a healthy hedge network, wildlife aside. Hedgerows are an asset for the numerous farm level and ecosystem level services they provide. Healthy hedgerows reduce soil erosion, as well as air and water pollution. They provide pollinating insects to pollinate our crops, predators to keep crop pests in check and shelter for livestock, reducing deaths from exposure and improving milk yields. Hedges help us fight climate change through storing carbon, and also reduce the damage from flooding. Hedgerows really do work for us.

The importance of well-connected, healthy hedgerows can’t be overstated, so it’s really important to protect them. Ultimately a well-connected network of hedges will help our native wildlife to survive and thrive.

To find out more about this beautiful and bountiful habitat, or to learn more about the survey, visit