Will exercise make me hungry?

When it comes to exercise, many of us find ourselves undoing all our hard work by indulging in a post workout feast — in fact, if you’re trying to lose weight, it’s off-putting to think that exercise might make you hungrier and more likely to cave in to an unhealthy treat.

But is this true?

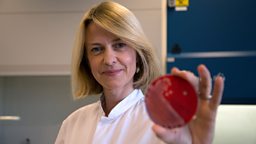

We enlisted the help of Dr Javier Gonzalez who specialises in exercise and nutrition at the University of Bath to find out whether exercise makes us hungrier than dieting.

The experiment

We took 10 volunteers and invited them to the University of Bath on two consecutive days. We split them into two groups – the diet group, and the exercise group.

Our participants all fasted for 12 hours before having their blood taken to measure the levels of a hormone called ghrelin – known as the ‘hunger hormone’ because it increases appetite.

Day 1

On the first day of testing we took baseline measurements. Each of our participants had a blood test to measure the ghrelin in their blood and then completed a questionnaire which asked them to grade their hunger on a sliding scale. The team at Bath University also measured the height and weight of each participant.

After an hour of rest everyone consumed a breakfast of muesli and milk equating to 800 kilocalories. Participants then rested for another 3 hours, completing another hunger questionnaire each hour, and then had a second blood test to measure their ghrelin levels again.

Day 2

The initial measures taken on day 1 were repeated on day 2, but afterwards the 10 participants were randomised into their 2 groups: exercise and diet.

Our exercise group were taken out to the University of Bath running track to burn off 500 calories - this involved running between 10 and 18 laps of the track depending on their weight and height.

Meanwhile, our diet group relaxed.

When breakfast time came, the exercisers had 800 calories as before. But the dieters’ meal was restricted by 500 calories, so they only had 300 calories each.

This gave both groups a 500-calorie ‘deficit’ compared with the previous day.

Then, after three hours, we took our measurements again to see whether the calorie deficit induced by exercise, or the one induced by diet, led to greater levels of hunger.

What we found

Although both groups had the same calorie deficit it was the diet group who reported feeling more hungry in their hunger questionnaires.

And in our ghrelin results, we found a striking difference.

This small study is consistent with a growing body of research suggesting that the idea that exercise makes us hungrier is a myth.

In fact, it actually seems to curb those hunger pangs.