Should I go gluten free?

Supermarket shelves are increasingly stocking ‘gluten free’ products, and with an estimated 8.5 million Britons trying a gluten free diet, we decided to carry out an experiment to find out whether gluten actually does affect some people badly.

Gluten is a protein that can be found in grains like wheat, barley and rye – which means it’s something that’s in a lot of foods most of us think as being staples of our diet: bread and pasta, not to mention pizza and cakes! So the obvious question to ask is why would you WANT to sacrifice all that good stuff?

Well, some people have to avoid gluten for very good health reasons. Around 1% of us have a condition called coeliac disease, although it’s estimated only 24% of these are diagnosed (see below on what to do if you think you have coeliac disease). If someone with this condition eats gluten their immune system sees the gluten as a threat and attacks the gluten which can lead to damage to the delicate wall of the intestines. If this continues, it can seriously affect the body’s ability to absorb nutrients. Coeliac disease sufferers may have symptoms ranging from gut disturbances to headaches or skin problems, but they may also show no symptoms at all. Fortunately, coeliac disease can be quickly diagnosed with blood tests, followed by a gut biopsy if these are positive, by your GP.

A very few people – around 0.1% of the population – have a wheat allergy. If they eat wheat, they suffer an immune response similar to hay fever - itching and sneezing. In very rare and extreme cases, it can cause anaphylaxis and be fatal. The allergic response is not triggered by gluten, but by other proteins found in wheat. However, choosing gluten free food is a simple way to avoid wheat altogether.

There is, though, a third group of people who are often described as being ‘gluten sensitive’, or ‘gluten intolerant’. These people can suffer symptoms that seem similar to some coeliac disease patients – pain or discomfort in the abdomen, tiredness, and irritable bowel – but currently science can’t identify any biological marker to account for these symptoms. This condition is now more commonly called non-coeliac gluten sensitivity, or NCGS, but the lack of biomarkers to explain NCGS has led some to ask whether these people are simply hypochondriacs.

So, does non-coeliac gluten sensitivity really exist? Do people really suffer when they eat gluten, and can this be verified by measurable changes in their immune system or inflammation?

Our experiment

We decided to set up an experiment to see if we could find out. 60 volunteers agreed to take part in the 6 week double blinded trial: for 4 weeks, the volunteers would be truly gluten free, but for 2 weeks we would slip gluten into their diet. Importantly, the volunteers wouldn’t know WHEN the gluten entered their diet, and nor would the scientists until after the analysis.

Before, during, and after the trial we took blood samples to measure various biomarkers in the blood – immune and inflammatory markers. We also asked them to complete a symptom questionnaire every fortnight to monitor any changes in how they felt throughout the trial. They were asked to describe how strongly they felt a range of symptoms commonly associated with NCGS – nausea, tiredness, abdominal pain, headaches, constipation etc.

At the end of the trial, we’d then be able to compare this log of symptoms and the blood results for each individual with the weeks when they were being given gluten, compared with the weeks when they were truly gluten free.

Symptoms

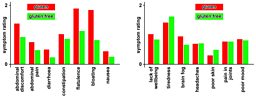

We asked people to record both gut symptoms (like bloating and nausea), and other health-related symptoms (like tiredness and ‘brain fog’).

With the gut symptoms, overall people suffered significantly more in the weeks where we introduced gluten into their diet compared with when they were gluten free.

With the other health symptoms, we found no significant difference between the gluten free and gluten containing weeks.

Results

Blood tests

The blood tests were designed to look for changes in the immune system and for specific markers of inflammation thought to be associated with the gut.

Our results found NO significant difference in any of the markers when comparing the weeks our volunteers were eating gluten with the weeks they were gluten free.

Nor were there any significant differences in the markers between those who reported symptoms and those who didn’t (we looked at one particular marker, CXCL10, that has been thought to be associated with NCGS).

What this means

We haven’t been able to provide a definitive answer to the question of whether NCGS “exists”. There’s good evidence from people that they feel gut symptoms when they eat gluten, and they feel much better when they give it up – but there could have been a placebo effect because people were trying to guess which pasta contained gluten. However, we found no blood markers that corresponded to these changes, or separated people who suffered symptoms from those who didn’t.

The fact that we didn’t find blood markers shouldn’t be taken to mean that there definitely isn’t a condition there – doctors and scientists know that there are conditions where blood tests are not conclusive or consistent. There are limitations to what we can find with blood analysis - there are hundreds of inflammatory markers, we only looked at a very specific handful, chosen because they had, in other research, showed a link with gluten, and of course, you can only find what you look for.

If you believe you suffer symptoms when eating gluten (or any other food), then a carefully monitored ‘exclusion diet’ is the recognised method of diagnosis. Your medical practitioner will first rule out coeliac disease, and then oversee an exclusion diet, asking you to log your symptoms while eating gluten, and then exclude it from your diet and again log symptoms, just as we did in our experiment (except you will have to get a friend to help if you want to do it ‘blinded’ – without know when you’re eating gluten – to minimise the placebo effect).

If you think you have coeliac disease, then the charity Coeliac UK say:-

If you think you may have coeliac disease, it’s essential to continue eating gluten until your doctor makes a diagnosis. The diagnostic tests for coeliac disease look at how the body responds to gluten and if you reduce or eliminate gluten from your diet, this is very likely to cause an inaccurate result for both the blood test and the gut biopsy.

Therefore, it’s essential to keep eating gluten throughout the diagnosis process. If you've already reduced or eliminated gluten from your diet, you will need to reintroduce it and as a general guideline, the recommendation is to eat some gluten in more than one meal every day for at least six weeks before testing.