Living alongside cobras

By researcher, Niall Stopford and snake specialist, Vishal Santra

I watched again as a cobra, with enough venom to kill 10 people, slithered within striking distance of a group of children walking to school. Both the snake and the children seemed totally unphased. I turned to Vishal, our safety guide and snake scientist, and asked, “Why do you think the cobras are so calm here?” He paused, pondered, then replied “It would take years of study from ecologists, zoologists, geneticists and anthropologists to even scratch the surface of how this tolerance has developed”.

When I first arrived in this small village in West Bengal, India, I was excited to see my first cobra, now these incredibly close encounters were a daily occurrence. Usually, venomous snakes are difficult to observe in the wild, if you do see one it’s often bolting from its age-old nemesis - the human.

The relationship between humans and venomous snakes has always been an uneasy one, many scientists believe a fear of snakes is hard-wired into our DNA, an adaptation we have inherited from our primate ancestors. But that fear goes both ways, a recent study suggests that African cobras evolved the ability to spit venom as a defensive response to our ancestors around the time they began to walk upright. With both hands free and the ability to strike at snakes with sticks, ancient cobras may have evolved to spit as a long-range defence mechanism.

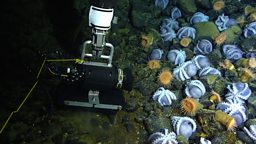

For the “Human” episode of Planet Earth III, we searched the globe for stories of wildlife adapting to the rapidly changing human-occupied world. Cobras hunting inside peoples’ houses and curling up underneath their beds at night to sleep… this story definitely fit the brief.

A highly venomous cobra hunts a toad through a village in India

In a small village in West Bengal, India, cobras coexist with humans.

It’s thought that the tolerance between the snakes and villagers here goes back hundreds of years. A local religious belief is held that the cobras are demi-gods, representatives of the snake goddess Jhankswari. The cobras are affectionately called “Old ladies” by their human neighbours and are revered to the point that only priests of the Brahmin caste are permitted to touch them.

Each day we would observe up to a dozen cobras moving calmly through the streets, intermittently flicking their tongues and probing the cavities of sun-cracked mud walls whilst the villagers carried on with their lives. It is thought that the unique religious tolerance of cobras has steadily changed their behaviour, they now move more slowly and are less likely to strike when disturbed.

They are here in the village to prey on toads and rats, and we wanted to document their hunting behaviour in this human-dominated environment. Each of our filming days began with children of the village running to us, calling out “jhanklai! jhanklai!” and pointing down shady alleyways at cobras on the prowl. We could tell instantly when a cobra was following the scent trail of prey, its body was taught and purposeful as it moved, its tongue flicking out regularly to pick up minute fragments of scent trails left behind by its unsuspecting prey.

Things heat up when the cobra finally tracks a scent to its point of origin, this is when the chase suddenly becomes dramatic and unpredictable. As the prey bolts, the cobra switches to using its vision and terrifyingly fast reactions to chase down and deliver a fatal injection of venom.

Witnessing cobras hunt made one close encounter particularly unnerving. One late afternoon I was kneeling down, filming close-up details of a cobra’s scales as it passed by. In the direct sunlight, the otherwise jet-black scales shone iridescent like an oil spill. I looked up and saw that the cobra was travelling toward a small courtyard ahead of me. I focused my attention on the camera screen I was transfixed… but then I felt something brushing against my knee. I slowly looked down to see the cobra had made a U-turn and was directly below me, probing the top of my boots with keen interest. I called Vishal, my legs frozen, to ask for his advice - “Don’t move” was his clear and only instruction.

Web exclusive: Living with cobras

Villagers in West Bengal explain how they live alongside highly venomous snakes.

Even with the exceptional tolerance, and calm behaviour of the snakes, accidents can happen. One morning we were talking to an older lady who showed us the scar on her foot, silvery and stretched tight like a drum. She explained that one morning, whilst opening her front door, a passing cobra got trapped underneath. In the panic it lashed out and struck her foot, amazingly it didn't deliver enough venom to be a fatal dose.

Filming these cobras was one of the most incredible experiences I have ever had. I was fascinated by the relationship between the cobras and the villagers. On leaving I was left with more questions than when I had arrived. How did this tolerance of cobras first arise? Who first saw them as religious beings, and how did they persuade others to change their attitudes towards them?! Over how many generations did it take the cobras to become calmer around humans? Despite not getting the answers, as I saw my last cobra slithering away into the undergrowth, I was glad that the natural world still had so many secrets left to uncover.

Vishal Santra – Lead snake expert on the filming trip.

India is known as the snakebite ‘capital’ of the world as nearly 60,000 people die from snake bites each year, and three times as many survive but are left with a permanent disability. As a conservationist at heart, it is particularly difficult for me to address the situation. Despite the loss of human lives, I know that it is extremely important to conserve snakes as they are often the apex predator and key in maintaining balance in the ecosystem. In addition, it is reported that the overall losses of grain to rodents in India are approximately 25% in the field and 25-30% in post-harvest food stores. This equates to a loss of at least 5 billion US dollars annually. Without snakes keeping their populations under control, this cost to farmers would be even higher.

There are, however, simple and cheap solutions that can dramatically reduce the incidence of snake bites in areas where snakes are present. If people are given rubber boots to wear whilst working in the fields, head torches to use at night, and mosquito nets to sleep under, then the risk of snakebite is far smaller.

Making Planet Earth III: Swimming with cobras

The film crew are on high alert when a cobra approaches children playing in a river.