Not your average crop-raider

By Jeremy Goss, Big Life Foundation

You might not know this, but you and an elephant likely share a taste for plants. Tomatoes? Check. Corn? Yup. Watermelon? Absolutely.

For most readers this will be little more than a cute observation but in Africa the reality has triggered an ongoing battle, one that the Planet Earth III crew threw itself into documenting alongside rangers in the Amboseli ecosystem of southern Kenya.

Elephants are big animals, needing a lot of space and a lot of food. So do we. Africa’s human population has exploded, more than doubling to 1.4 billion people in the last 30 years. The other part of the equation - space available - is of course unchanged. The result is an increasing battle for resources between two species that have similar needs.

The 2-million acre Amboseli ecosystem is a microcosm of this issue. Laid out beneath Mt Kilimanjaro, Amboseli is home to one of the best-known elephant populations in the world, having been studied by the Amboseli Trust for Elephants since the early 1970’s.

While elephant numbers have plummeted across much of Africa, community-focused conservation efforts in the Amboseli ecosystem have played a central role in the remarkable recovery of the elephant population, from approximately 400 in the 1970’s to almost 2,000 now.

But like the rest of Africa, Amboseli is changing fast. Agriculture is expanding, consuming space and water. Humans need to eat of course, but elephants do too. Where once there were lush swamps full of elephant food, now there are smallholder farms.

Understandably, elephants invade those farms to get at the nutritious crops growing there. The Planet Earth III team were there to capture night-time ‘raids’, where in a matter of hours an elephant can wreck a farmer’s entire season’s crop, and with it his ability to feed his family.

In the dry seasons these raids occur multiple times nightly across the ecosystem and at one-point estimates for total annual damage ran into the millions of dollars; a huge burden for low-income communities.

And so, farmers try to defend their property and source of income. Spears are thrown in desperation, and when they hit their elephant targets, they injure or kill. Just as problematic is the resulting intolerance of elephants. Trying to conserve a species in the face of local community resistance is an uphill battle.

There is no bad guy in this situation, only a need for solutions. This is where . Big Life is an Amboseli-based non-profit organisation that put human communities and their needs at the centre of efforts to conserve wildlife and natural habitats.

Big Life employs 360 community wildlife rangers, who work just as hard to mitigate human-wildlife conflict as they do to prevent poaching. These are the people who step out into the darkness each night, to patrol the interface between humans and elephants. Dedicated ranger units spend the night on the move, searching for shapes in the darkness, trying to pre-empt the conflict, or waiting for calls of distress from the community. Using only torches and thunderflashes (noisy pyrotechnics) to scare away the elephants, these men take on a dangerous job that few would - standing up to elephants in order to protect them.

With patience, hard work and new low-light technologies, the Planet Earth III team were able to capture footage of the dramatic night-time scenes as these rangers try to prevent elephants from raiding farms.

The work that rangers do is saving farmers crops and elephants’ lives, but it is a band aid. Chasing elephants around in the darkness is unsustainable, and rangers cannot be everywhere at once along an interface that stretches hundreds of kilometers. There is a better solution.

Starting in 2017 Big Life set out to create a hard boundary between the two worlds, constructing 100km of electric fence to separate farmers and elephants. Powered by solar energy, the fence was immediately effective and has reduced elephant crop-raiding by more than 90% where it has been installed; farmers in these areas no longer spend nights in their fields in fear of losing an entire season’s produce, and retaliatory killing of elephants is down.

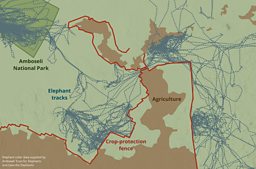

The map below shows how effectively an electric fence has prevented just three collared elephants from entering farmlands (data kindly provided by the Amboseli Trust for Elephants).

the most effective way of securing a long-term future for elephants in Amboseli

The fence is expensive to construct and maintain, with annual maintenance costs of approximately $2,000 per kilometre, and large areas of unprotected farmland still need protective barriers in future.

However, managing human-wildlife conflict is fundamental in an ecosystem that is home to humans and animals, and fences will be the most effective way of securing a long-term future for elephants in Amboseli.