Relax! Not specialising early could be your key to success

There is a widely held belief that to be successful you have to specialise early and focus all your efforts in one area. To dabble or delay just means getting left behind. Or does it?

In Don’t Tell Me The Score, the best-selling author David Epstein explains why the best way to succeed is to sample widely, gain a breadth of experiences and take detours. It’s never too late for a career change or to discover that new hobby you love. You might just be amazing at it.

David Epstein interview

David Epstein talks to Simon Mundie about the 'early specialisation' myth. Listen to the interview.

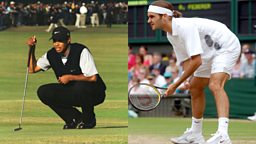

The Tiger Woods versus the Roger Federer model

Tiger Woods’s path to success is the stuff of legend. He was so “physically precocious” says David, that by the age of ten months he was imitating his father’s golf swing. By two he had appeared on national television demonstrating that swing, and by 21 he was the greatest golfer in the world.

Federer didn’t specialise in tennis until he was a teenager.

Roger Federer’s development story, in marked contrast, is little-known. The multiple Grand Slam winner was also a keen young athlete but he played basketball, badminton, table tennis, handball and football – and he swam, wrestled, skated and skied. He didn’t specialise in tennis until he was a teenager.

In exploring which of these paths is the norm for those who go on to excel, David was intrigued to learn that, perhaps surprisingly, it was the Federer model.

“Pretty much everywhere you look, in pretty much every sport, athletes who go on to be elite have what scientists call a sampling period where they play a wide variety of sports,” says David. “They learn these general physical skills that scaffold later learning, they learn about their own interests, they learn about their own abilities and they systematically delay specialising until later than peers who plateau at lower levels.”

Broad experience is the key for success in life, not just sport

In venerating the Tiger model of success – both inside and outside of sport – it seems we’ve been backing the wrong horse.

“Golf is an outlier of a skill compared to most other sports… and most other human activities,” says David, “so in many ways it’s a particularly poor example that we’ve been extrapolating from.”

Golf, he says, is a “kind learning environment.” All the information is available, patterns repeat, next steps are very clear and you get automatic feedback. Other sports are more dynamic: you have to anticipate what another player or ball is going to do, you face challenges you’ve never previously faced and your next steps are not always obvious. This, David explains, is a “wicked learning experience.”

This “wicked” experience better mimics real life itself, which is more unpredictable and challenging than any sport. In golf you might be able to specialise early and narrowly, but in wicked domains we need to set up a broader set of skills, says the writer. “Breadth of training predicts breadth of transfer”: train broadly and you will build conceptual skills that you can then apply to every new situation you find yourself facing.

No knowledge or experience is wasted

In changing career, you bring knowledge from one area where it’s ordinary, into another where it’s less familiar – and potentially extraordinary.

If you’re not sure what career is right for you, and you’ve been jumping around between jobs, don’t panic, says David. Every role you do, every experience you have, is adding to your broad spectrum of skills – and you never know when they might come in handy.

Steve Jobs, the tech titan and founder of Apple, once attended a calligraphy class. It was this experience that gave him the idea of developing attractive fonts and customisable elements for the Mac.

And “in technological innovation,” says David, “the people who are making the biggest impact now are not the people who have spent their lives working in one technology, but the people who have spread their work across a large number of different technological domains.” This means they are able to bring knowledge from one area where it’s ordinary, into another where it’s less familiar – and potentially extraordinary.

It’s never too late

Van Gogh had multiple careers: art dealer, teacher, bookseller and pastor. It was only when he had failed at all these things that he turned his hand to drawing, and it was only in his final years that the impressionist found the style that made him famous. “If not for the last two years of his life he may have been a historical footnote,” says David.

Recent research shows that in the United States, the average age of a blockbuster start-up founder is 45-and-a-half. “They usually have to zigzag quite a bit before that, before they find that ground where they can do something uniquely,” says the writer, “but just like with the Roger and Tiger story, we only hear of these very young people and these very dramatic successes – even though those are not the norm.”

Don’t be afraid to change your path

“Don’t fall prey to the sunk-cost fallacy,” says David. Just because you’ve already invested a lot of money or effort into something doesn’t mean you should keep going. Changing jobs means a “period of challenge” but usually when people make the leap they improve in all sorts of ways. “If you’re thinking about making a change,” says David, “you probably should.”

We also shouldn’t be scared to alter our plans and visions for the future. With a five-year plan we’re making decisions for a person we don’t know yet, to be carried out in the context of a world that we can’t conceive of yet. “I think it’s fine to have a five-year plan,” says David, “if you hold it very lightly and are willing to update it a lot.”

In his new book, “Range”, David Epstein dispels the myth that specialism beats generalism in sport and in life.

More from Don't Tell Me The Score

-

![]()

Range: David Epstein

Why it's better to be a generalist than a specialist in sport and life with David Epstein.

-

![]()

Fame: Boris Becker

Fame has its benefits but comes at a big cost, as Wimbledon legend Boris Becker explains

-

![]()

How to overcome fear

Tips from the world’s best free solo climber

-

![]()

Seven tips for succeeding in life from a champion ultra-runner

Jasmin Paris talks to Simon Mundie about commitment and cake.